On the fifth morning of our 25-day van trek along the Santa Fe and Oregon National Historic Trails this spring, my partner Leslie and I rose early and took a short hike across a landscape of despair.

We had spent the previous night in a unit of the Comanche National Grassland south of La Junta, Colorado, at a recreational area known as Vogel Canyon. The trail we followed from our campsite led across exposed bedrock and then dipped into a shallow drainage slicing through stony ground studded with junipers. About half a mile in, where the creekbed widened into a small valley clad in dry grass and shrubs, we came to the ruins of a house and barn built from rough-hewn sandstone blocks.

According to an informational panel placed there by the U.S. Forest Service, the rubble was all that remained of the Westbrook family homestead. Like many thousands of American families, they had come to the Great Plains in the late 1800s or early 1900s to claim public land in one of the greatest grasslands on Earth, and to carve out a living by farming and running cattle on it. Also like many thousands of other families, they failed, and in the process became participants and victims in the greatest human-caused ecological catastrophe in American history.

There are 20 national grasslands in the United States, totaling about 4 million acres. Seventeen of them are on the Great Plains; one each is in Oregon, Idaho and California. All of them are a reflection of the calamitous cascade of events that eventually produced the Dust Bowl of the 1930s.

The proximate cause of that catastrophe was a combination of poor farming practices and a multi-year drought, which together turned what had once been biologically productive and resilient native grasslands into dry, barren soil that could be ripped from the ground by the unceasing prairie winds. Rising as much as 20,000 feet into the air, these enormous clouds of choking dust swept eastward to the Atlantic, darkening the skies above New York and Washington, D.C., depositing a layer of grit on the desks of stockbrokers and senators. As journalist and author Timothy Egan recounts in his riveting history of that era, The Worst Hard Time, the Dust Bowl at its peak encompassed 100 million acres, the majority in the Southern Plains, and a quarter of a million people fled its ravages in the 1930s. The Westbrook family was among those who left the land in that decade.

But other factors besides drought and poor farming practices contributed to the disaster. Also playing a role were ill-advised federal land policies, global market forces, a fundamental ignorance bordering on delusion about the true nature of the Great Plains ecosystem, the development of new and powerful agricultural technology, and simple greed.

After we left our camp that morning and headed for Kansas and Missouri, we would be given ample opportunities to reflect on how the collision of those forces a century ago shaped the countryside along the Santa Fe Trail in the decades that followed its demise as a trading route.

What lies beneath

After a visit to Bent’s Old Fort National Historic Site, which I wrote about in the previous installment of Next Chapter Notes, we followed the Arkansas River into Kansas, where we soon found ourselves crossing mile after mile of vast farm fields that were either still winter-bare or just sprouting a crop. It was hard to tell what those tiny green nubs would eventually become, but I assumed it was wheat, corn, barley or something similar, judging by the proliferation of towering grain elevators (“prairie skyscrapers” in the Plains vernacular) along the rail line that linked the small towns along our route like beads on a string. We also passed countless modern variations of the prairie skyscraper: Fields of enormous generator turbines, transforming the insistent Great Plains wind — which had driven a generation of settlers crazy and powered the Dust Bowl disaster — into electrons and dollars.

Along the way we pulled off the road at a large sign advertising “Santa Fe Trail Wagon Ruts,” a site that one of our guidebooks assured us was “perhaps the largest and best preserved in Kansas.” These traces of wagon passage worn into the prairie soil more than 150 years ago are common attractions along both the Santa Fe and Oregon trails, and this was our first real opportunity to check some out. We pulled into the large parking lot and followed a paved path to the top of a rise, where there were several historical markers and signs.

But no ruts, alas. The hillside was still clothed in last year’s dead grass, 3 to 4 feet tall, which obscured the ground’s surface and any wagon traces it might still bear. But the prairie view in the soft light of evening was a fine one.

We stopped for the night in Dodge City, where we checked in to a motel for our first shower since we’d left home five days earlier. We then enjoyed unexpectedly good Mexican takeout from a taco truck moored in a parking lot at the hardware store next door. (If you ever find yourself in Dodge City at dinnertime, I recommend you check out Don Taco.)

The next day the road led us to the junction of the trail’s Cimarron and Mountain routes, where we stopped to visit Fort Larned National Historic Site. Unlike Bent’s Fort, which was a privately owned trading post, Fort Larned was a U.S. Army post, established to protect traders, mail carriers and military supply wagons in the 1860s and 1870s from raids by Great Plains Indian tribes.

After half a century of contact between indigenous tribes and white Americans along the trail, much had changed in their relationship. The steady increase in westward-bound settlers along the Santa Fe and emigrant trails, and new federal polices toward native tribes, had disrupted their access to traditional hunting grounds for bison, the center of physical and spiritual life for the Plains people and the foundation of their economy. Travelers and settlers also had introduced exotic diseases that decimated the native population, and the bereaved survivors were increasingly being forced onto reservations. It is no surprise that interactions had become more hostile.

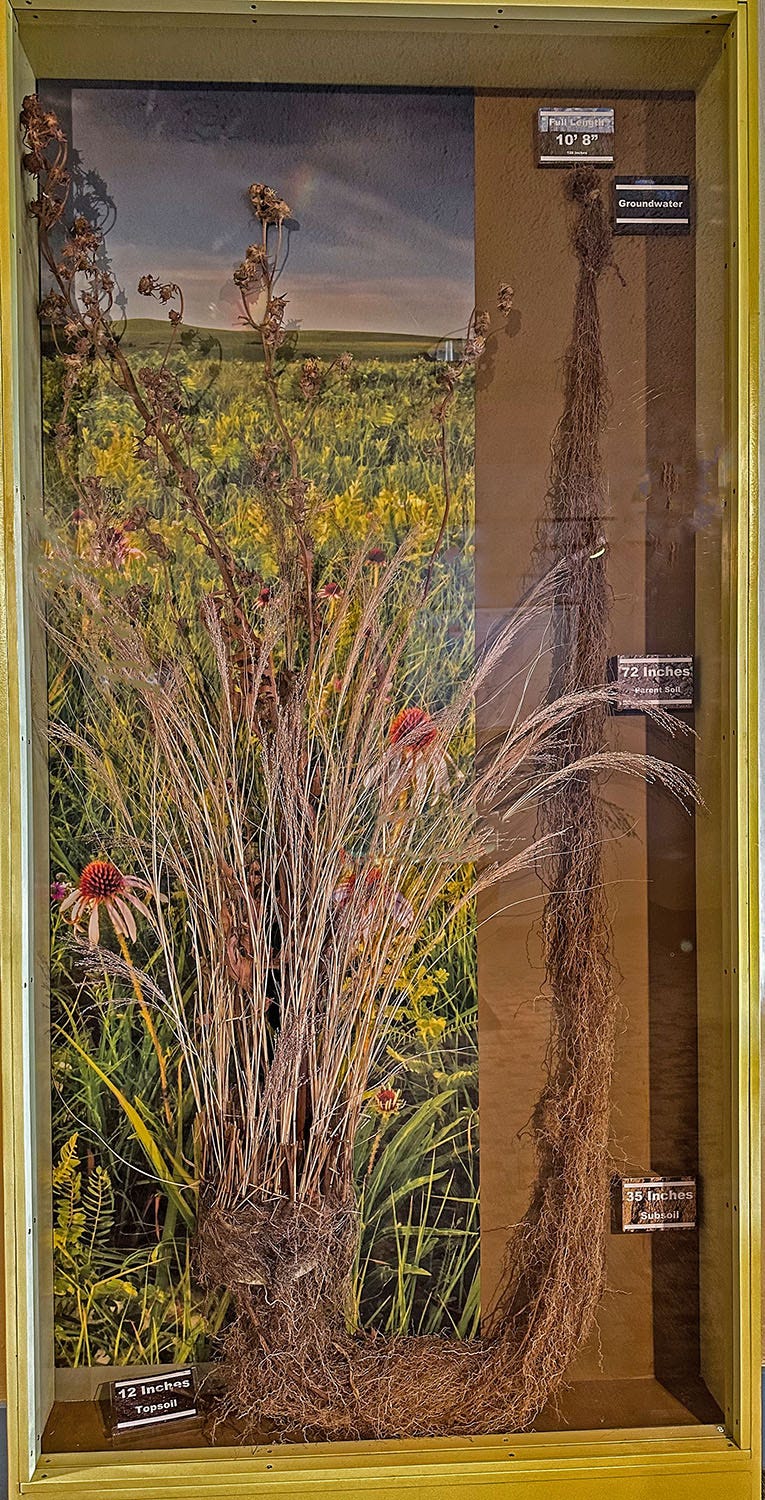

We reached the fort in a flurry of late-season snow, and headed straight to the heated visitor center, where we found informative exhibits about the increasing tensions, conflicts and violence that began to engulf the Santa Fe Trail landscape in the late 19th century. One display that captured our attention, however, related to our morning hike: A glass-front case containing a dried clump of native prairie grasses and cone flowers with their attached root system — all 10 feet and 8 inches of it — demonstrating how the dense underground web of tough fibers would have stitched together soil and subsoil while also enabling the plants to withstand periodic drought by sponging up every available molecule of water.

Fort Larned is only a few miles from where the 100th meridian of longitude crosses Kansas from north to south. This is, roughly speaking, a point of climatological transition in North America. East of it, average annual rainfall generally exceeds 20 inches and unirrigated agriculture is possible. West of it, particularly on the Great Plains, it is not. That region is semi-arid, and although there may be several wet years in succession, eventually the pattern regresses to the mean and drought parches the land. The relatively wetter Eastern Plains were the realm of the tallgrass prairie, its big and little bluestem, switch grass and Indian grass reaching heights of 6 feet. Around Fort Larned the ecosystem shifted to the mixed-grass transitional prairie, and to the west lay the shortgrass prairie, which we explored on an earlier trip. That was the landscape where homesteading farmers suffered the most in the 1920s and 1930s.

The last stand

From Fort Larned, we drove to Council Grove, which takes its name from the label given to an oak grove on the banks of the Neosho River by George Sibley, who negotiated a treaty there with the Osage tribe in 1825 guaranteeing safe passage through their lands for Santa Fe Trail traffic. Sibley was the head trader at Fort Osage, near today’s Independence, Mo., and led a commission tasked by the federal government with conducting a formal survey of the Santa Fe Trail, which they carried out in 1825. It’s a small, quiet town with a park near the river where the stump of the oak under which Sibley is reputed to have negotiated the Osage treaty is protected by fencing and a roof.

Our camp for the next two nights was just outside of town in the Council Lake State Recreation Area’s Santa Fe Trail Campground. We generally shy away from developed campgrounds when we are on the road, but there’s not much in the way of public land in Kansas and Hipcamp sites are similarly sparse. We had a nice site with a view of Council Lake, which is impounded by a flood-control dam built by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers in 1960-64 near the headwaters of the Neosho River. Our campsite, liberally serenaded by northern cardinals and other birdlife, was the indirect product of the federal government’s response to catastrophic flooding that struck the area in 1951.

Here's how the National Weather Service described it in a 30th anniversary analysis of the event, which it called “one of the greatest natural disasters ever to hit the Midwest”:

May, June and July of 1951 saw record rainfalls over most of Kansas and Missouri, resulting in record flooding on the Kansas, Osage, Neosho, Verdigris and Missouri Rivers. Twenty-eight lives were lost and damage totaled nearly 1 billion dollars. (Those were 1951 dollars; adjusted for inflation the total would be $12 billion today.) More than 150 communities were devastated by the floods including two state capitals, Topeka and Jefferson City, as well as both Kansas Cities.

The next day, we headed south on the Flint Hills National Scenic Byway to the Tallgrass Prairie National Preserve, which protects a minuscule remnant of an ecosystem that once covered 140 million acres of North America. Just 4 percent of the original tallgrass prairie remains, about 11,000 acres of it in the preserve, which is mostly owned by The Nature Conservancy and co-managed by it and the National Park Service. (The word prairie is French, meaning “meadow,” derived from the Latin pratum, which also means “meadow.”)

The basement of Kansas is Permian limestone, 250 million years old, the product of an ancient sea that once covered much of interior North America. In the Flint Hills, a lovely undulating landscape that contrasts sharply with the state’s generally pancake-flat topography, that stony substrate lies just inches below the ground’s surface, resisting both erosion and the steel plow. It’s the reason the preserve’s remnant native grassland survived the orgy of gouging and planting that turned a million acres of American prairie into wheat fields each year from 1925 to 1930. In the preserve, tallgrass makes its last stand.

To those who crossed Kansas in the 1830s, the notion that the vast Great Plains bison herds and the grassland that sustained them would be gone a century later, and that all that land would be farmed by homesteaders, would have sounded delusional. On the earliest pioneer maps, everything on the Plains west of Council Grove — which had the last stand of hardwoods travelers from the East would have seen until they reached the Rockies — was labeled the “Great American Desert.” The earliest waves of westbound settlers hurried across it as quickly as possible.

Stephen Long, a U.S. Army topographical engineer who led the first American scientific expedition across the Great Plains to the Rockies, wrote in his 1820 expedition report that “In regard to this extensive section of the country, I do not hesitate in giving the opinion that it is almost wholly uninhabitable by a people depending on agriculture for their subsistence.”

Possessing the Plains

So. What changed?

Incentives, for one thing. In 1862, President Abraham Lincoln signed into law the Homestead Act, which provided that any adult citizen, or intended citizen, who had never borne arms against the U.S. government (this was during the Civil War, after all) could claim 160 acres of surveyed government land (320 acres for a married couple). Claimants were required to live on and “improve” their plot by cultivating the land. After five years on the land, the original filer was entitled to the property, free and clear, except for a small registration fee.

That same year, Lincoln also signed into law the Pacific Railway Act, which granted cash subsidies and enormous tracts of public land to the Central Pacific and Union Pacific as inducement to construct the first transcontinental railroad. Subsequent legislation authorized similar deals for three other transcontinental lines, thereby handing over 174 million acres of the public domain to railroad companies, which could only profit from those lands by inducing settlers to head west and buy them. Which the railroads and their allied boosters did, typically by providing assurances of the land’s productive capacity and salubrious climate that were entirely fictitious.

Homesteaders and speculators initially focused on the fertile, well-watered landscape east of the 100th meridian, particularly the choicest tracts along valley floors and rivers, wisely avoiding the semi-arid lands to the west. To encourage settlement of those more benighted parts of the public domain, Congress passed the Enlarged Homestead Act of 1909, which increased the maximum individual homestead claim to 320 acres (640 acres, or one square mile, for a married couple) of non-irrigable land in parts of Colorado, Montana, Nevada, Oregon, Utah, Washington, Arizona, and Wyoming.

And then there was World War I, which began in 1914 and resulted in the military blockade of a critical shipping route that shut Europe off from Russia, producer of most of the continent’s wheat and other grains. The United States stepped in to make up the loss, and the increase in demand sent wheat prices soaring. In response, Great Plains farmers — now with access to powerful machines that had replaced the horse-drawn plows and threshers of the 19th century — ripped up nearly every square inch of native prairie to plant grain.

Profits were high in the first few years, an anomalously wet period, which incentivized more farmers to plant still more grain. Inevitably, however, prices fell after the war ended in 1918 and Russia re-entered the global market. In response, American farmers planted even more, trying to make up in volume what they were losing in per-bushel revenue. By the 1920s, more than 120 million acres on the Plains were planted in grain.

Then came the Great Depression, which caused banks to fail and dried up the credit farmers had used to buy tractors and expand their plantings. Then came multi-year drought, fierce and unrelenting.

The single worst day of the Dust Bowl was Black Sunday, April 14, 1935. The storm that barreled out of the Southern Plains that day, in Timothy Egan’s memorable telling, “carried twice as much dirt as was dug out of the earth to create the Panama Canal. The canal took seven years to dig; the storm lasted a single afternoon. More than 300,000 tons of Great Plains topsoil was airborne that day.”

The wind-blown grit from that and countless other “dusters” buried cropland, buried houses, choked cattle and humans alike. Thousands fled; thousands more stayed because they really had nowhere else to go.

Retreat

In 1937, Congress passed the Bankhead-Jones Farm Tenant Act, which contained numerous provisions, including a loan program to help tenant farmers buy land, particularly in the American South. But in the Great Plains, its most significant element was authorization for the U.S. Department of Agriculture “to develop a program of land conservation and land utilization, including the retirement of lands which are submarginal and not primarily suitable for cultivation, in order thereby to correct maladjustments in land use. In order to effectuate this program the Secretary of Agriculture is authorized to acquire by purchase, gift or devise, or by transfer from any agency of the United States or from any State, Territory or political subdivision, submarginal land and land not primarily suitable for cultivation, and interests in and options on such land.”

In essence, the federal government launched a program to buy failing Dust Bowl farms, and to rehabilitate the ruined land by planting grass and trees. Between 1938 and 1941, according to a report published in 1942 by the USDA’s Soil Conservation Service, which was tasked with developing and implementing the program, the government purchased 4.5 million acres of such land at a total cost of $18.3 million — an average of $4 an acre, or about $88 in today’s dollars.

The Westbrook family homestead near our campsite in Vogel Canyon was among those “submarginal” lands acquired by the Soil Conservation Service (known today as the Natural Resources Conservation Service). Administration of this vast patchwork of retired farmland, nearly all of it in the semi-arid Western Plains from North Dakota to Texas, was transferred to the U.S. Forest Service in 1960, reorganized and renamed as National Grasslands.

The contrast between the ruined homestead we hiked in Comanche National Grassland and the Tallgrass Prairie National Preserve could not be more stark. Before the National Park Trust acquired it in 1994, the preserve land was a working cattle ranch, established in 1878 as the Spring Hill Farm and Stock Ranch and passing through a succession of owners over the next century. The founders, Stephen and Louisa Jones, bought the land from the railroad, and used it to fatten young cattle brought there from their Colorado ranching operation.

Grazing free on abundant native grasses, the animals gained weight rapidly and profitably, and the Jones family used their wealth to build a remarkable complex of structures on the ranch. Constructed of native limestone, these included an enormous barn and a large house built in a distinctive architectural style. They plowed the fertile deep soil of bottomlands for crops and left the rocky prairie alone for cattle to graze, except to periodically burn off old grass to make room for new — a tactic that had been employed by the Pawnee, Kaw, Osage and Wichita people who originally inhabited the area and relied on the vast herds of bison that roamed it. Both natives and bison had been driven from the land by the time the ranchers arrived.

The National Park Trust later transferred a small portion of the land to the National Park Service and the majority to The Nature Conservancy. The partners have reintroduced bison and prescribed burns as a management tool.

During our visit, we toured the huge barn and the main house, and then went for a hike across the rolling prairie. I wish I could say we were treated to the tallgrass in all its glory, but we were a bit early in the growing season. What would be a profusion of grasses up to 6 feet tall by fall was mere nubbins in April.

Still, it was green and expansive, and wildflowers were already in bloom. We eventually had to cut our hike short because the resident bison herd was grazing right next to the trail, and park guidelines call for maintaining at least 300 feet from the unpredictable animals. (Nevertheless, Leslie was able to shoot the video above.)

We watched from a distance as bison calves charged around, and adults rolled in the dusty wallows they’d worn into the grass. It was a blue-sky day, with a constant but tolerable wind, and the viridescent prairie reached to the horizon in every direction. This is what it once was like everywhere in the Great Plains, and although there was hope and beauty in this preserved landscape, over it all hung a cloud of lament for what has been lost.

Coming in Part 3: Onward to Missouri and the eastern terminus of the Santa Fe Trail.

Wow, John, I had no idea about the dust storm in 1935. Thanks for so much interesting information from your trip. I always enjoy your explanations of your travels. Again, looking forward to the 3rd installment. Great photos too.

Jill