This episode of Next Chapter Notes begins with fluffy cows and ends with baby goats. If animals are not your thing, don’t worry — there’s also plenty of non-critter stuff to come.

The previous installment of this journal found my partner Leslie and I camped outside of Council Grove, Kan., after our side trip to the Tallgrass Prairie National Preserve. In that precious remnant of an ecosystem that once occupied 140 million acres of North America we had encountered a small herd of bison, which we took care not to approach. Adult bulls weigh a ton, are notoriously sensitive to violation of their personal space, and can run 30 mph.

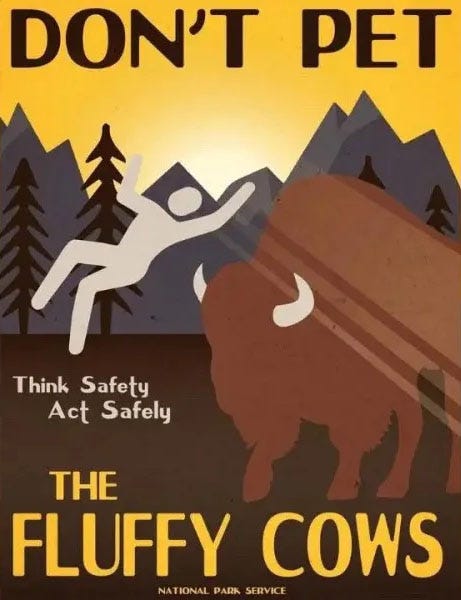

Unfortunately, a minor but consistent number of visitors to parks with resident bison are not similarly cautious, resulting in the occasional goring or trampling — most commonly in Yellowstone National Park — and this recently led the National Park Service to launch a cheeky outreach campaign warning park visitors not to “pet the fluffy cows.”

So we didn’t. After enjoying them from a safe distance, Leslie and I headed back to our lakeside camp. The next day, we continued east across Kansas and then picked up Interstate 70, following it across the Missouri River into Missouri.

When we crossed the river it was running high and muddy, and it was shocking to see so much water after our long, dry crossing of the Plains. The landscape grew steadily greener and lusher as we continued toward St. Louis, leaving the semi-arid western Great Plains and the land of the Dust Bowl far behind.

At some point, we noticed that the farms we were passing no longer had the big center-pivot irrigation systems ubiquitous on the Western and Central Plains, where unsustainable pumping from the vast Ogallala Aquifer system has enabled modern farmers to banish the recurring droughts that doomed their predecessors in the 1920s and 1930s — and potentially setting them up for a similar disaster when the groundwater runs out. In fact, we could see no evidence of irrigation at all as we reached the eastern part of the state, no stacks of pipe, no wellheads, no canals or reservoirs. This apparently is what agriculture looks like in a land where it rains every month and 41 inches a year (the St. Louis average), so unlike our home terrain in Ventura County.

Although not technically a stop on the Santa Fe Trail, St. Louis was intimately linked to it. Before they made their way into the freight haulers’ wagons, most of the goods those traders transported along that 1,000-mile road of commerce traveled first on riverboats along the great watery highways — the Ohio, the Mississippi, the Missouri — that knit together the young nation. St. Louis was the great staging area, the gateway to the West, where manufactured goods from New England, agricultural products from the Midwest and South, eventually even luxury items imported from Europe, were offloaded, transferred to wagons, and began their overland journey toward Mexico and the frontier.

In St. Louis, we checked into our Airbnb, an 1833 brick row house converted into charming apartments, near the city’s downtown. It was within walking distance of Gateway Arch National Park, and we spent the next day exploring the park’s remarkable museum and visitor center.

At just 91 acres, Gateway Arch is America’s smallest national park. Until 2018, it was known as Jefferson National Expansion Memorial, and the Museum of Western Expansion beneath the signature arch focused on the Louisiana Purchase of 1803 and the exploration of that vast new territory by Meriwether Lewis, William Clark and their Corps of Discovery, which helped open it to American settlement. But along with its new status as a national park, Gateway Arch’s museum and visitor center underwent a substantial enlargement and complete makeover, part of a multi-year, $380 million renovation that also connected the park to the city and its waterfront. It reopened in 2018 with a much broader and more nuanced focus on the role St. Louis played in the nation’s history over the past two centuries.

The picture it paints is often a sobering one.

Indigenous continent

Gone is the unabashedly celebratory perspective on the “opening” of the West and its eventual settlement by mostly white Americans that the museum presented the last time I visited, at the beginning of my 2001 journey along the Lewis and Clark Trail. The museum now features six galleries, one of which still focuses on Jefferson’s vision of a continental nation and the Louisiana Purchase. Others, however, provide more critical geopolitical, cultural, economic and historical context.

One gallery is devoted to St. Louis in the colonial era, and its role in the struggles over possession of North America by England, Spain and France. Another looks at the city’s role in commerce, as the gateway to trade, exploration and settlement of the West, and another gallery extends that examination to the rise of the industrial age. There’s also a gallery focusing on the process that created the landmark Gateway Arch itself and the national memorial it anchored.

But the most radically recast focus is on display in the “Manifest Destiny” gallery, which trains an unblinking eye on the painful reality that realization of Jefferson’s continental vision for the United States, besides requiring bold initiative, perseverance and sacrifice by explorers and settlers, also involved a war of conquest against Mexico and the functional equivalent of genocide against North America’s indigenous peoples.

The exhibit I found most compelling there was a huge video screen displaying a looping animation that showed how occupation of North America changed over time, from first European contact to the modern day. Bit by bit, what was initially an indigenous continent — every corner of it fully inhabited by people whose ancestors had arrived thousands of years earlier — was transformed, colors on the map changing to indicate where new Euro-American settlement had displaced native occupation.

Steadily, the indigenous landscape fragments and shrinks, as tribes are forced from their homelands and eventually, in a burst that lasts only a decade or two, confined to reservations, which appear suddenly all over the West. And then, in the final frames of the animation, we see those reservation lands — granted to the tribes by treaty with the U.S. government — whittled away to practically nothing between 1887 and 1900, after Congress passed the General Allotment Act. The law enabled to government to allot lands originally granted to tribal groups to individual tribal members instead, and because the surviving tribal members were so few and the individual allotments were so small — 80 acres per person in many cases — much of the tribal land remained un-allocated. The government then declared this to be surplus federal land, and sold it to white settlers.

In just moments, as the map animation enters the 20th century, the indigenous presence on the landscape nearly blinks out.

We would carry that indelible sequence of images with us as we traveled west in the coming days. Along the way we would visit many places that told local versions of this story — tribal visitor centers, reconstructed military forts, small-town history museums — and some would do it well while others would fall short. Honest reckoning with the non-mythical version of Western history is unevenly distributed across the landscape.

We would also be reminded that, far from vanishing, native tribes remain an integral part of the cultural landscape of the modern West, many of their communities finding new ways to tell their stories and to assert their right to participate in management of the region’s vast inventory of public lands — all of which were once indigenous lands.

But before we could embark on our journey west along the Oregon National Historic Trail we needed to rejoin and say goodbye to the Santa Fe Trail.

The end of the trail

The founders of Franklin, Mo., platted the town on the Missouri River flood plain in 1816. A decade later, the river rewarded their lack of foresight by flooding the community. It did so again two years later, this time washing most of Franklin away. The town’s residents proved they could take a hint by moving what remained to higher ground 2 miles away and starting over.

The original town was named, for no obvious reason, in honor of Benjamin Franklin. The new town was named, for an obvious if not particularly imaginative reason, New Franklin. And so it remains today, while historians refer to the abandoned 1816 town site (now a corn field) as Old Franklin. Confusingly, there is also a town immediately to the southwest of New Franklin named just plain Franklin, which until it was granted that name by the county in 1912 had previously been known variously as Franklin Junction and Junction City but otherwise had little in common with the Old or New Franklins except proximity.

This little corner of Howard County, Missouri, may have identity issues.

Old Franklin is noteworthy to history buffs as the place where William Becknell and four companions set out on Sept. 1, 1821, with a string of pack mules bearing trade goods, and headed west toward Santa Fe. Their inaugural journey established the profitable feasibility of commercial trade overland between the United States and Mexico’s northern settlements, and Franklin’s distinction as the birthplace of one of the most important western wagon roads of the 19th century rubbed off on New Franklin. That is where travelers today will find a red boulder in the center of town bearing a plaque that commemorates Becknell’s trek and proclaims (New) Franklin “The Cradle of the Santa Fe Trail.”

The marker awkwardly occupies a parking strip in the middle of Broadway Avenue with traffic lanes on both sides. It was placed there by the Daughters of the American Revolution and the state of Missouri in 1909, when there was probably less automobile traffic than there is now. Although there’s not really a lot today, either.

New Franklin is a quiet town of about a thousand people, surrounded by farm fields, and perhaps its best feature (besides its historical significance) is that it lies along the Katy Trail — a 237-mile rail-to-trail conversion that turned the old Missouri-Kansas-Texas Railroad (MKT) line into a biking and hiking path that crosses most of the state. (“Katy” is sort of a shorthand phonetic version of “MKT.”) For half its length it hugs the bank of the Missouri River, which makes it a good way to travel along part of the Lewis and Clark National Historic Trail. I bicycled a segment of the Katy when I visited Missouri on my 2001 reporting trip retracing the explorers’ trail, and remember not only the scenery but the heat and humidity of June, and the fact that the path’s surface of crushed limestone left my sweaty legs white with dust.

The day we stopped there in April, we also visited nearby Arrow Rock. That entire village, founded in 1829, has been declared a National Historic Landmark, and it’s like a picturesque time capsule of early 19th century architecture. The Missouri River flows nearby, although not as near as it once did; the unruly Missouri has shifted its channel many times over the centuries, and the site of the Arrow Rock ferry landing where Becknell’s party crossed the river on their way to Santa Fe in 1821 is high and dry now.

By the time we reached New Franklin, and the conclusion of the first stage of our 25-day National Historic Trails trek, Leslie and I had been on the road in our camper van for 10 days. We had crossed California, Arizona, New Mexico, Kansas and Missouri, and a bit of Colorado.

We spent that night in a Hipcamp site on a goat farm, which provided an immensely entertaining end to our day thanks to the presence of a crowd of energetic baby goats, bleating and bounding around like furry little windup toys. The next day, we would leave the goats and the Santa Fe Trail, and move on to Independence, Mo., home to the National Frontier Trails Center and the starting point for pioneers bound for the West. We now had the Oregon Trail before us, stretching 2,200 miles across plains, rivers and mountains, with unknown adventures yet to come.

Coming in Part 4: The Platte River Road.

I remember your first chapter in the Lewis & Clark series began in St. Louis.

John, Wow so fascinating! I am truly enjoying my history lesson which includes great photos. The goats are the icing on the cake...so cute and they hop not walk. Too darn cute. Looking forward to Part 4! Thanks for sharing your travel with all of us. Hi to Leslie! Hoping her wrist has healed well.

Jill