Stories of Stone

Following a trail of antiquity through Nevada and Utah

If I put much stock in omens, I would have been seriously worried about embarking on our recent road trip to Utah.

The morning my partner Leslie and I were to depart for nearly three weeks exploring the redrock canyon country (including a week rafting the Green River, which I wrote about last month), I spent several hours loading gear, clothing, food, beverages and other consumables into our camper van. Next Chapter was parked near the entry to our house in Ventura, and each transfer required a clumsy hands-full round trip through the heavy front door, which we never leave standing open because we keep our cats — Jinx, Boo and Sprinter — inside at all times.

I had made several of these cycles without incident, but as I returned to the house from the van one more time, something brought me up short: A snake was slowly slithering from the landscaped yard onto the concrete landing in front of the door. As it reached the doormat it stopped, squarely blocking the doorway. Thinking at first that it was one of our resident gopher snakes, which we see fairly often on the ranch and appreciate for their contributions to rodent management, I approached for a closer look.

That’s when it swiftly coiled up in a defensive striking position on the mat, and rattled its tail.

Unnerved, I backed away, walked around the house and entered through the garage downstairs. Southern Pacific rattlesnakes are fairly common in Ventura County, but we had never seen one before in our yard, let alone on our literal doorstep. Through the big windows that flank the front door, we could see that the snake remained coiled just outside and seemed in no hurry to be anywhere else. It eventually stretched out and began slowly exploring the paved outdoor entryway and its decorative assortment of rocks collected on our camping trips.

That cats had never seen a rattlesnake at the front door either. Once they noticed the novel movement outside the window, they rushed to investigate. This led to a weird dance: felines on the inside, fascinated and alarmed in equal measure, the snake outside putting its nose right up against the glass and flicking its tongue in and out, likely puzzled by its inability to catch any scent of the strange animals it could see just inches away.

To many people, having your trip prep disrupted by a venomous viper could be regarded as a bad sign. I thought of it, however, as a promising — albeit temporarily inconvenient — visitation from the wild world. We were about to spend 20 days in some of the most remote and rugged country in the West, and if I ascribe any symbolic importance to the scaly apparition on our doorstep, it would be that it was serving as an emissary of all those fascinating creatures that crawl, slither, hop, creep, soar, flap or lope across the unforgiving landscape we intended to explore. Perhaps it was appropriate that it settled first on our welcome mat.

Land on fire

The rattler eventually slithered away, as snakes do, having found nothing to hunt on our paved landing. It vanished without hurry into the lush landscaping of our yard, hopefully on its way to the surrounding avocado orchard and its abundance of rats and mice. I resumed my packing routine, keeping an eye out for the snake’s possible return, and after lunch we hit the road.

We divided the first leg of the trip to eastern Utah into four segments, stopping for the first night at a campsite we’ve used before in Mojave National Preserve. It was 105 degrees and windy when we pulled off Interstate 15 outside Baker, and knowing that would be the case we had timed the drive so we rolled in to camp just before sunset, as the desert furnace was beginning to cool down.

The next day took us to Valley of Fire State Park in Lake Mead National Recreation Area, just north of Las Vegas. We’d reserved a site in a developed campground there for two nights, planning to spend the layover day hiking to some noteworthy petroglyph panels and taking in the area’s dramatic scenery.

Our site in Arch Rock Campground was spectacular: an alcove just big enough for our van, carved into walls of Aztec sandstone. The rock, lithified remnants of a Jurassic dune field, had been worn by wind and water into baroque fantasy of nooks, towers, arches and fins, and it glowed campfire-red in the angled light of approaching sunset. For good measure, a juvenile desert bighorn sheep came casually wandering by as we were settling in, like a camp host checking on new arrivals — another emissary from the wild, though decidedly less alarming than our rattlesnake.

The next day we drove to a trailhead a few miles from camp and hiked into Fire Canyon Wash. Our objective was the Mouse Tank petroglyphs, one of two main rock-art sites in the park (the other is at Atlatl Rock, near a campground of the same name).

It was hot in Valley of Fire, too, though not as dangerously as it would be later in the summer. The week we were there, the park closed eight of its longer trails, as it does annually from May 15 to Sept. 30.

“These trails have a history of frequent medical calls, search and rescue missions, and fatalities during this time of year,” according to the park website. “Unfortunately, the demand is more than we are able to safely manage.”

For good measure, trailheads offer helpful warning signs about the risk. I’ve never visited a park, local, state or national, that addresses the possibility of hyperthermia so dramatically.

Art at the boundary

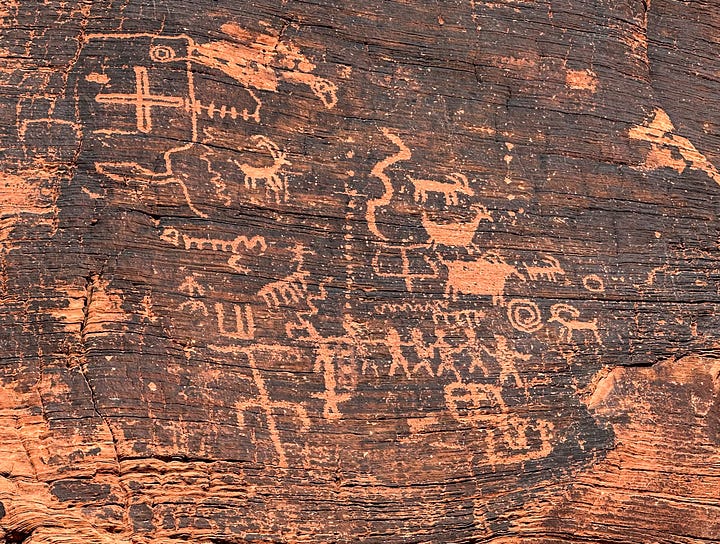

There are several petroglyph panels in Fire Wash, pecked into desert varnish on the enclosing cliff faces, some precariously high above the wash’s sandy floor. The rock art at both Valley of Fire sites is unusual in featuring three styles linked to very different cultures and time periods. The park is located in a transition zone between the Great Basin desert of Nevada and eastern California, and the arid canyons of the Colorado Plateau in Arizona and Utah; the petroglyphs may reflect how different groups with different traditions and subsistence strategies moved across this boundary region over time as the climate changed.

The majority are the work of people who occupied the area from about AD 1 to AD 1200 and were similar in many ways to the ancestral Pueblo of the Colorado Plateau — living first in small clusters of seasonally occupied pit houses and eventually in larger fixed villages associated with cultivated cropland. It’s not clear whether this represents a cultural evolution on the part of the archaic hunter-gatherers typical of the Great Basin, who were the earliest inhabitants of the Valley of Fire area, or a northward migration of ancestral Pueblo people into the edge of the Great Basin, displacing the previous residents. Eventually, as drought intensified between AD 1200 and AD 1300, the farmers retreated south and Valley of Fire became home to ancestors of the Southern Paiute.

At Atlatl Rock and Fire Wash, the work of all three cultures — archaic hunter-gathers, ancestral Pueblo farmers, and ancestral Paiute hunter-gatherers — is represented. Some of the petroglyphs may date to the historic period, after Spanish explorers began wandering around the Southwest; others may be as old as 1,500 years,. Atlatl Rock gets its name from the large petroglyph of a throwing stick hunters employed to hurl spears at large game before introduction of the bow and arrow, which in North America began in about 500 AD.

Because of its proximity to Las Vegas, Valley of Fire State Park is often crowded, and as we drove the main park road after our hike, parking lots at scenic viewpoints were clogged with vehicles, including tour buses. For all that, the campground was reasonably quiet, even though it was full both nights we were there. But we were happy to be on our way the next morning, for we were headed to an equally spectacular landscape where we anticipated considerably fewer people.

Into the swell

Our third outbound travel segment carried us from the broiling desert into the decidedly more alpine landscape of Utah’s Pahvant Range, where we found a boondocking site above cottonwood-lined Clear Creek in Fishlake National Forest. It was cold and drizzling as we set up camp, although the rain broke long enough for the sky to deliver a nice sunset.

The next day we headed for the San Rafael Swell in south-central Utah, stopping first at Fremont Indian State Park to inspect its significant concentration of rock art. (We would later encounter more Fremont art while floating through Desolation Canyon, which I wrote about in the previous installment of Next Chapter Notes.) The wet, blustery weather persisted, dropping a peculiar form of hail called graupel on us as we lunched in the van, and we later found ourselves driving Interstate 70 over the Fish Lake Mountains through a sudden snowstorm, an unusual event for mid-May. It was intense enough that some drivers pulled over to wait it out, while others (including me) slowed to about 40 mph and set our hazard lights to blinking.

We soon drove out of the squall and descended into the dramatic landscape of the swell, one of the most scenic and least visited of all Utah’s natural features. It’s a great dome, roughly kidney-shaped, 75 miles long and 40 miles wide, pushed skyward 40 million to 60 million years ago during the same mountain-building episode that raised the Rockies. Its colorful layers of sandstone, mudstone, shale and limestone have since been eroded into a tortured tangle of canyons, buttes, gorges, badlands, valleys and mesas. At the eastern edge of the uplift lies the San Rafael Reef, a thousand-foot wall of scalloped stone pierced by scores of canyons that would take years to explore.

Interstate 70 bisects the swell from west to east, passing directly through the reef in an impressive series of road cuts. On this day, however, we turned off before we reached the reef and followed a series of unpaved roads south into the heart of the swell, one of the wildest and most beautiful neighborhoods in Utah’s redrock country. We are drawn back to it year after year, and on this occasion we made our way to a boondocking site we had scouted on a previous visit. It was set on a small rise, in a grove of junipers and pinyon pines, with a fine view across many miles of open desert.

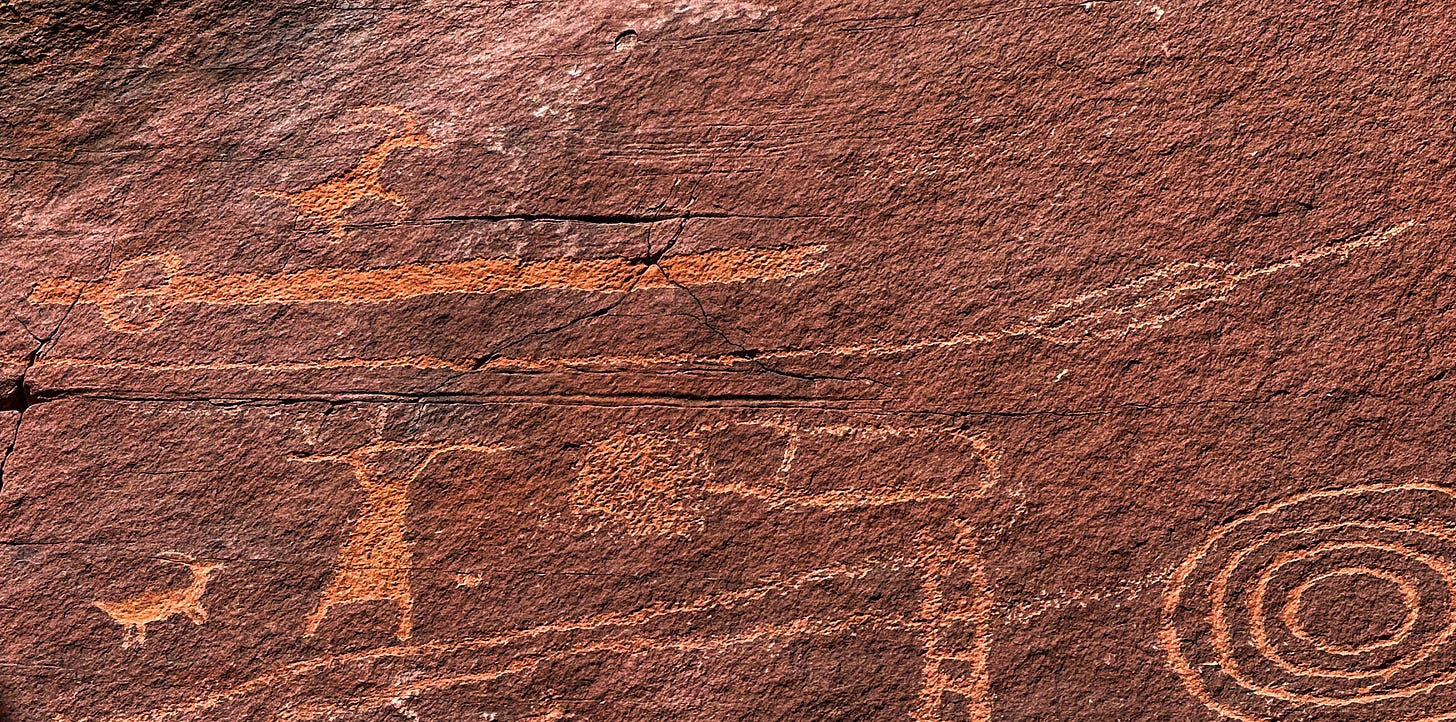

Our plan for the next day was to ride mountain bikes along the dirt road from our campsite, through a cramped underpass beneath I-70 — too low for our van to pass through, as we’d discovered on a previous trip — and a couple miles more to a noteworthy pictograph panel on a sandstone formation north of the highway known as Locomotive Point.

It did not go as planned.

We loaded up the bikes with lunch, water and a first aid kit, and set off from camp. We quickly discovered that the unpaved road was mostly surfaced with deep sand, which made pedaling and steering both risky and exhausting. We made it maybe a mile before we turned around, dumped the bikes in camp and drove the van to the impassable underpass, where we parked, ate lunch, and set out on foot.

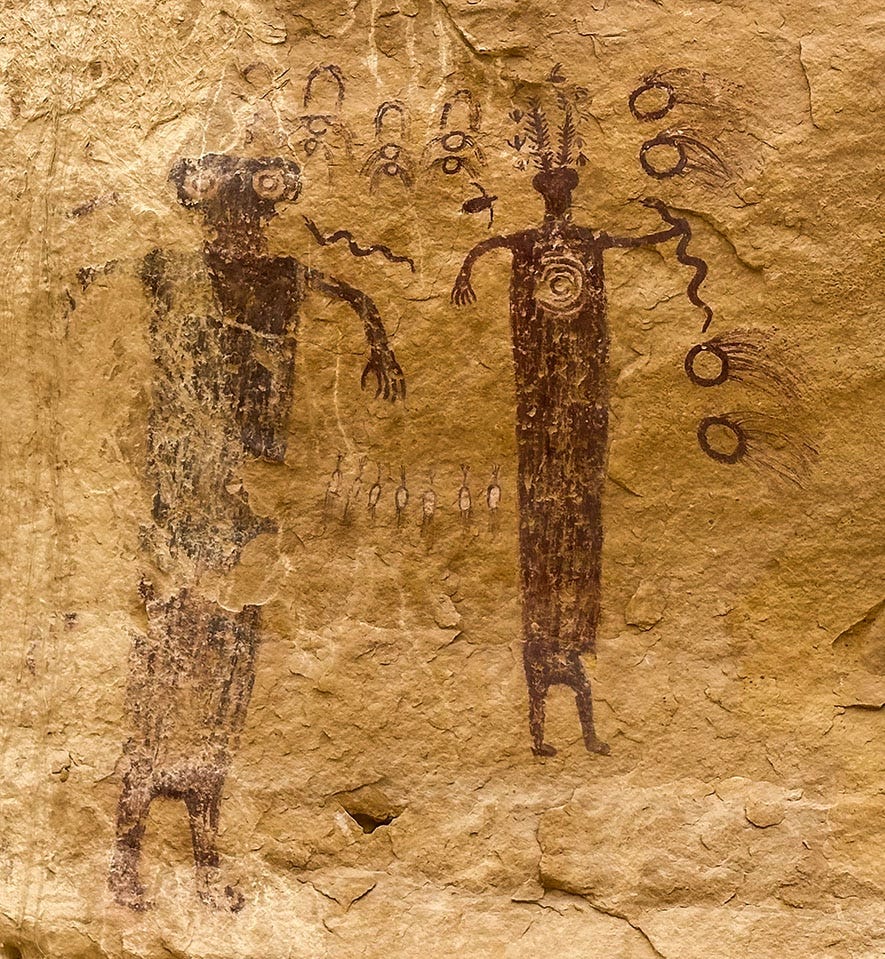

And the rock art was worth the walk, despite the occasional sprinkles and gusts from an unsettled sky. There are two pictograph panels painted in red on the golden Wingate sandstone of Locomotive Point, and the images are eerie and enigmatic. They’re a type known as the Barrier Canyon style, after the location where the most famous pictographs of that family may be found: the Great Gallery (in what was later renamed Horseshoe Canyon), an isolated unit of Canyonlands National Park. We visited it in 2019, and photos from that trip, which predated our acquisition of Next Chapter and the launch of this journal, can be found here on my website.

Barrier Canyon style pictographs are distinctive, typically featuring elaborately decorated humanoid figures with long tapered bodies. Archaeologists believe them to be among the oldest examples of Indigenous rock art in the Southwest, likely the product of archaic hunter-gatherers who roamed the region 3,000 years before the present. That’s a long time ago, but it bears mentioning that they were painted on a 200-million-year-old canvas. Antiquity is a relative thing in the canyon country.

As is always the case, it’s impossible to know for certain what was going on in the mind of the artist who created the Locomotive Point paintings, which include figures with elaborate headdresses, snakes, what appear to be comets, and a row of pronghorns viewed from behind. We were content, however, simply to submit to their spooky beauty. Full understanding might be nice, but haunting ambiguity has a power all its own.

Behind the reef

The day after our trek to Locomotive Point, we began making our way to the town of Green River and our rendezvous with the ARTA guides who would row us through the rapids in Desolation Canyon. On our way out of the swell, we detoured to visit Swasey’s Cabin, a crude log structure built in 1921 by Joe Swasey, whose family arrived in the 1880s and ran cattle. It was buzzing that day with off-highway vehicle traffic, an occasional obstacle on the dirt-road network that spiderwebs the region.

A week later, having returned to Green River after our river trip concluded, we headed back into the swell. This time we were aiming for an area farther south, where the aptly named Behind-the-Reef Road provides access to the heads of canyons that pierce the San Rafael Reef.

We drove to a boondocking site off the road to Goblin Valley State Park, one we have used before, and were surprised at how many fifth-wheels, RVs, trailers and vans were clogging the dispersed camping areas along the way. Only belatedly did we realize that in losing track of the days during our languid week on the river, we had forgotten that we would be heading back into the swell on Friday of the long Memorial Day weekend.

We found an acceptable site for the night, but there were too many neighbors. The next day, after scouting along Behind-the-Reef Road and hiking from there a short distance into Wild Horse Canyon, we relocated to a far superior site just inside that canyon’s mouth.

We were surprised to find the site so quiet, because to reach it we drove past enormous holiday-weekend encampments crowded with jumbo motorhomes, tent compounds, trucks hauling trailers loaded with off-road vehicles. But by venturing a bit further, into nooks and crannies of the swell that big rigs could not navigate, we were able to find privacy and one of the best non-river campsites of the trip.

There’s an enduring lesson in that, which informs much of our traveling: You often will find good things — or at least solitude — if you’re willing to push on a little further than most people, whether driving on a dirt road or sauntering along a trail.

Triassic trees

It was difficult to leave the next morning, the campsite being so beautiful and the canyon begging to be explored further. But it was Leslie’s birthday, and we had a celebratory dinner reservation that evening more than 110 scenic but slow miles away. So, we reluctantly broke camp and hit the road.

Our route took us out of the swell on Highway 24, through Capitol Reef National Park to the town of Torrey, where we turned south onto Highway 12, a legendary engineering feat that offers one of the great scenic drives of the West. We followed it up and over Boulder Mountain, where the highway tops out at an elevation of 9,200 feet — at the summit, aspens were still winter-bare and snow patches lined the road — and then down a long swooping grade into the hamlet of Boulder.

We’d booked two nights at Boulder Mountain Lodge, and had dinner reservations both nights at the adjacent Hell’s Backbone Grill. The lodge is one of our favorite places to stay in Utah, and the restaurant is perhaps our favorite place to eat in all of the West. This is as much because of its great origin story as it is for the creative and brilliantly executed menu, which features locally sourced ingredients, including fruit and produce from the on-site farm. (I wrote about it at length in this May 2023 post.)

We checked into our room, which had a view of the pond and bird sanctuary behind the lodge, and then enjoyed a wonderful meal in the restaurant. Afterward, we enjoyed a glass or two of wine on our room’s balcony while watching bats flutter above the pond and snatch bugs from the twilight sky.

The next morning, we set out on our final exploration of the Utah canyon lands, following the Burr Trail Road out of town and into Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument. Burr Trail drops off the town’s mesa into Long Canyon, where it winds between towering red walls before climbing onto a bench in the Circle Cliffs. (I shot the video below through the windshield as we were driving through the spectacular canyon.)

Our objective was the Wolverine Petrified Wood Natural Area, where a 225-million-year-old fossil forest — second-largest of its age in North America — lies in a wash carved into the Chinle sandstone cliffs. It lies along the unpaved Wolverine Loop Road, which intersects Burr Trail Road about 15 miles from Boulder, circles counterclockwise around the perimeter of bowl-shaped White Valley, and rejoins Burr Trail Road 20 miles later.

It is possible to make a 30-mile loop of the drive, but that is not necessary to reach the main concentration of petrified wood, which is about 10 miles down Wolverine Road from its first intersection with Burr Trail. But it you miss that first turnoff — perhaps because you are relying on Google Maps for directions instead of referring to a detailed paper map, and the Google Maps robot voice inexplicably fails to direct you to turn right at that first intersection — you will, indeed, spend a few hours kicking up dust and rattling your teeth and everything in your camper van on 20 miles of washboard dirt before reaching the petrified trees and making your way back to pavement.

We’d thought about doing the entire loop, knowing how spectacular the landscape is from a previous visit to the area. We just didn’t plan to do so, thinking we would not have enough time.

Turns out we did, and fortunately, it was a nice day for a long, slow drive. And the petrified forest was worth the visit, a fitting place to end our outdoor Utah adventures before a last night in Boulder and the start of the trek home.

The petrified wood of Wolverine Canyon is not like the crystalline candy-colored specimens in Arizona’s vastly more famous Petrified Forest National Park, or even Escalante Petrified Forest State Park just 30 miles down Highway 12 from Boulder. Wolverine’s fossil wood is mostly jet black, standing out vividly from the intense red-orange of the Chinle cliffs and their erosional debris. Chunks of it are scattered all over the ground about a mile from the trailhead parking area, and so are the petrified trunks of entire trees, lying where they fell along the banks of a semitropical river at the dawn of the age of dinosaurs.

Opportunities to conjure a vanished world abound in the grand geological wonderland of southern Utah, whether that is the world of Triassic conifers in Wolverine Canyon, or that of the ancestral people who lived their lives, dreamed their dreams and left painted or pecked records of their visions, wishes and beliefs on countless canyon walls.

There are stories everywhere. You just need to know where to look.

💕Your description of your travels are like a beautiful novel. And, your photos and videos are equally spectacular.

Thank you for sharing.

I thoroughly enjoyed reading in its entirety.

🌹Rosa Lee