Magnificent Desolation

Journeying into the heart of Utah's redrock wilderness

“After dinner we pass through a region of wildest desolation. The canyon is very tortuous, the river very rapid, and many lateral canyons enter on either side. They usually have their branches, so that the region is cut into a wilderness of gray and brown cliffs ... Piles of broken rock lie against these walls; crags and tower-shaped peaks are seen everywhere, and above them long lines of broken cliffs; beyond the cliffs are pine forests of which we obtain occasional glimpses as we look up through a vista of rocks. The walls are almost without vegetation; a few dwarf bushes are seen here and there clinging to the rocks, and cedars (junipers) grow from the crevices — not like the cedars of a land refreshed with rains, great cones bedecked with spray, but ugly clumps, like war clubs beset with spines. We are minded to call this the Canyon of Desolation.”

— John Wesley Powell, The Exploration of the Colorado River and its Canyons (1895)

One hundred and thirty years later, John Wesley Powell’s name for that landscape still sticks, and from the air this reach of the Green River canyon looks every bit the “region of wildest desolation” he described.

My partner Leslie and I flew over Desolation Canyon in mid-May in a four-seat Cessna 172 operated by Redtail Air, a tour and shuttle company based in Moab, Utah. Chief company pilot Chris was at the controls, and the fourth seat was occupied by Scotty Ewen, a guide with ARTA River Trips and leader of the six-day springtime rafting adventure we were about to begin.

Taking off from a lonely airstrip outside the hamlet of Green River, Utah, the small plane headed north and climbed steadily to clear the Tavaputs Plateau, which rises more than a mile above the river and reaches an elevation of more than 10,000 feet. Below us a sea of stone stretched away in every direction, carved sinuously and deeply by the erosive force of the Green River, the longest tributary of the Colorado River. Rising among glaciers in the Wind River Range of Wyoming, the Green winds 730 miles from its birthplace in the Northern Rockies to a confluence with the Colorado in the desert heart of Utah’s Canyonlands National Park.

Our destination was a primitive dirt landing strip about 84 river miles north of Green River, on the canyon rim above the Bureau of Land Management boat launch at Sand Wash. As we traced in rapid reverse the leisurely river journey that would occupy most of the coming week, Chris and Scotty provided narration through our headsets, noting landmarks, tributary canyons, geological formations, places we likely would camp and hike.

About 40 minutes after takeoff, our small plane banked, shed speed and altitude, and bounced to a halt on a ridge overlooking the river. Waiting for us there were the other three guides on our trip — Nikki Best, Rose Garrett and Emily Pearlman — who loaded our gear into an ARTA truck for the drive down to the launch.

Our gear rode, but we hiked. It was about a mile and a half, with an 800-foot descent, along a rocky trail from the airstrip to the boat ramp. We arrived to find the rafts rigged and loaded, waiting for us to board. Which, after the standard safety talk and trip orientation from Scotty, we did.

And then we pushed off into the current, to begin one of the most beguiling river trips I’ve ever experienced.

Meet Uncle Gusty

Our water-borne journey through Desolation Canyon, smack in the middle of one of the largest roadless areas in the Lower 48, was the centerpiece of a nearly three-week adventure in the heart of Utah’s vast redrock country. The rafting trip was bracketed by days spent camping and exploring on foot, by camper van and — briefly and unpleasantly (more on that in a future Next Chapter Notes installment) — on mountain bikes, around the San Rafael Swell and Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument.

The journey included sunny days, days with clouds and wind, days marked by rain, snow, hail, lightning and graupel; there were deep canyons, ancient rock art panels and old homesteader cabins; there were bighorn sheep, clouds of chittering birds and starry new-moon nights of endless black-velvet depth.

But at the heart of it all was the river.

Our journey down the Green was my 26th whitewater rafting trip, my 17th with ARTA, and it was unlike any that came before. A typical commercial rafting trip involves 15 or so guests and generally six guides, but for this — the first Green-Desolation launch of the season for ARTA — Leslie and I were the only paying passengers who had signed up. Normally a trip that small would not launch, but we had received a call a couple weeks before our departure date from an ARTA manager who wanted to reassure us that the trip was still on despite our solo status, and to make sure we were OK with spending six days alone with four guides on 18-foot oar boats.

A professionally run private river trip with two guides for each passenger? We were more than OK with it. That’s pretty much a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity.

The only drawback was that because our crew was so small, there would be no paddle raft. Typically this is a 14-foot boat with a guide at the stern to steer and give commands, and four or six passengers with paddles to provide propulsion, and that’s where most of the fun and excitement is in whitewater. It is by far our preferred way to run any river. But sitting high and (mostly) dry on a padded gear box while someone younger and stronger than us did all the work sounded appealing, too. We’re retired, after all. Besides, if we really felt the need to get soaked in a rapid, inflatable kayaks would be available.

At the Sand Wash launch, Leslie and I opted to join Rose in her boat for our first stretch on the water, planning to rotate through Nikki’s and Scotty’s rafts as the days went by. Emily’s boat was off limits to us — Utah regulations require that a guide row a river at least once before carrying passengers down it, and this was her first time on this reach of the Green. (The opportunity to train an ARTA guide on a new river at the start of a new season may have been behind the company’s decision to greenlight our undersubscribed journey.) But we would have plenty of time in camp to get to know her, too.

One of the challenges of launching at Sand Wash is that the initial stretch of river is flatwater. Our first day covered just over 18 miles, and for most of that distance the feeble current provided our rowing guides little motive assistance. In fact, the ferocious up-canyon wind that rose in the afternoon made it a real slog; pause the oars for a moment and the rafts would halt and then seem to back upstream.

Even John Wesley Powell, in his Exploration of the Colorado (the published version of his journal notes from several river expeditions) remarked upon the winds of Desolation Canyon:

“The wind annoys us much today,” he wrote on July 8, 1869. “The water, rough by reason of the rapids, is made more so by head gales. Wherever a great face of rocks has a southern exposure, the rarified air rises and the wind rushes in below, either up or down the canyon, or both, causing local currents.”

Wind is our nemesis while we are driving Next Chapter down an interstate, and it can similarly bedevil anyone rowing or paddling watercraft down a river. And like us when we are behind the wheel of our adventure van, river guides have a quasi-superstitious habit of refusing to refer to that meddlesome phenomenon as “wind,” as if it were an evil demon that could be summoned merely by uttering its name. Scotty’s euphemism of choice was “Uncle Gusty,” which we immediately adopted and will no doubt use on all future adventures.

The first day on the water taught us something besides a new nickname for wind. With all due respect to the intrepid Major Powell, Desolation Canyon from river level appears anything but desolate.

Into the unknown

John Wesley Powell was a one-armed Civil War veteran, wounded at the battle of Shiloh, who led several pioneering survey expeditions by wooden boat through the Green-Colorado river system between 1869 and 1872. Although European and American explorers and adventurers had visited and described some parts of the Colorado River watershed long before then, the river stretch in the great tangle of canyons between southern Utah and Arizona — among them the Grand Canyon itself — had at that time never been systematically explored or mapped. The objective of Powell’s “Colorado River Exploring Expedition” was to rectify that.

It was an unusual project for its time. Federal government surveys had crisscrossed much of the West by the late 19th century, some undertaken for military reasons, others for commercial purposes, seeking routes for wagon trails and railroads, or mapping mineral deposits, timber, rangeland and potential farmland. But although Powell secured some federal support, he also cobbled together financial backing from a variety of national, state and local scientific institutions, natural history museums and universities. He was a private civilian, as were the other men on the expedition. And his interests were exclusively scientific: geology, archaeology, ethnography, botany, hydrology.

Powell’s life story is important to understanding the history of the modern West, and there are several fine books to choose from if you wish to delve deeper into his biography, or learn more about the mad adventure that was his expedition’s first journey down the Green and the Colorado. Powell’s own report is one, but I also recommend Wallace Stegner’s classic Beyond the Hundredth Meridian (1953) and Donald Worster’s mammoth Powell biography, A River Running West (2001).

The first Powell expedition launched May 24, 1869, from the town of Green River in Wyoming Territory (not to be confused with Green River, Utah, our Cessna-powered departure point). Powell chose that location because the transcontinental railroad, completed just two weeks earlier, crossed the Green River there, and provided the most expeditious way of transporting their cumbersome boats and gear from the East into the Colorado watershed.

The “desolation” Powell reported finding here did not really mesh with our experience of the canyon. As we slipped downstream on that first day, we found the river’s sandbars and benches lined with slender willows, towering cottonwoods, bright green box-elders. Junipers marched up the steep slopes, and in moist alcoves high on the north-facing canyon walls there were stands of enormous ponderosa pines.

It is harsh country, to be sure, but also stunningly beautiful. And I suspect that Powell’s impression, inspiring the name the canyon still bears, was a result of the contrast between the deep rock-walled chasm he found there and the 100 miles of river that preceded it, which traverse a broad, verdant valley. It’s now covered with farms and pastures, but in 1869 that valley was a patchwork of wooded islands, marshes, and lakes that supported a wide variety of birds and wildlife.

Also, he and his crew may just have been tired, bruised and cranky. By the time Powell and his nine men, traveling in four wooden boats, reached the approximate location of Sand Wash and the launch point for our own four-boat flotilla, they had been running the river for more than six weeks. They had been battered, swamped, tossed violently about, and made generally miserable at times by the force of rapids and weather along hundreds of miles of moving water.

It's impossible to avoid the ghost of J.W. Powell on the Green and Colorado river canyon systems, because nearly all their geographic features bear names bestowed by him and his crew. Far upstream of Desolation in Lodore Canyon, for example, there’s a noteworthy rapid known as Disaster Falls — the site where, a month before they reached Desolation, one of the Powell expedition’s boats crashed into a rock and split in two, the fragments then being dashed to pieces as churning current and waves flung them against more rocks. The men aboard survived, but much equipment and food were lost. (“Lodore” is also a Powell naming.)

We camped that night on a sandy bench above a nearly vertical landing, which made us doubly glad that younger and more agile people than us were in charge of getting gear off the boats and setting up camp. And we were also happy that river-running techniques and gear have improved considerably since Powell’s day.

The rhythm of the river

The next day dawned sunny but cold, with scattered clouds, and grew increasingly gray and chilly as the hours and miles passed. We stopped twice to hike to petroglyph panels, a minor one at a landmark named Mushroom Rock and a much more impressive set in Flat Canyon, 6 miles downstream.

They were the work of people archaeologists refer to as members of the Fremont Culture, which describes neither a linguistic nor a tribal grouping but a mixed population spread out over a vast area of Utah, Nevada, Colorado and Idaho that broadly shared certain traits: common styles of pottery, basketry, rock art and footwear, a reliance on both farming and hunting/gathering for subsistence. They are believed to have inhabited the area from about 500 AD to 1300, meaning that although the Powell expedition’s journey is often referred to as the first exploration of the Colorado/Green canyon county, Indigenous people had lived there more than a thousand years earlier.

We made 14 miles that day in Nikki’s boat, and pulled in just below Flat Canyon rapid to set up camp. While we were doing so Uncle Gusty showed up with all his cousins, nieces, nephews and friends, bearing lightning, thunder, rain and hail — skin-stinging horizontal hail, driven by a sudden microburst that blasted through the canyon.

Within moments everyone was soaked. Leslie and I abandoned our efforts to set up our tent; we were in the middle of that process when the squall rolled in and drenched it inside and out before we could get a rainfly up, submerging our chosen site in a large puddle for good measure. The guides hastily erected a popup canopy to shield the kitchen and us, and then worked to hoist a larger tarp, propped up by 10-foot oars and lashed securely to nearby trees, to shield a larger area so we’d have someplace dry to gather and dine.

The squall was over in about an hour, our tent being the only casualty. Fortunately, there was a dry spare in one of the gear bags, so we were able to start over in a better spot.

Once the excitement had died down, we were able to appreciate the campsite’s beauty. Spacious and shaded by large cottonwoods, it featured a beach landing and expansive views of the canyon walls, which rose steeply above the Green and caught the golden light of sunset after the storm clouds had passed. We enjoyed an expertly prepared dinner — always a high note of any day on the water, and consistent point of pride for ARTA guides — without any further interference from the Gusty clan.

The next morning dawned cold, and we bundled up as we enjoyed coffee and breakfast, and began breaking down the camp. Day three of a rafting trip is usually when “river time” sets in, a sort of languid pace for each day centered around simple markers: the wakeup call of “Coffee!” as the sun is coming up, pushing off into the current as the morning warms, pulling over midday for lunch or a hike or both, running a rapid or two or three, eddying out for the night’s camp. It’s the day when calendar and clock evaporate, the rhythm of the river takes hold, crew and guests become a sort of temporary family, and you lose track of whether it’s Monday or Wednesday or Friday, and who the hell cares because the only things that matter are what lies around the next bend and what you can see, hear and smell right now as the boat drifts in the current or surges forward with the oarlock creak of muscle power.

It's why we were there. It’s why we go back.

Goodbye to new friends

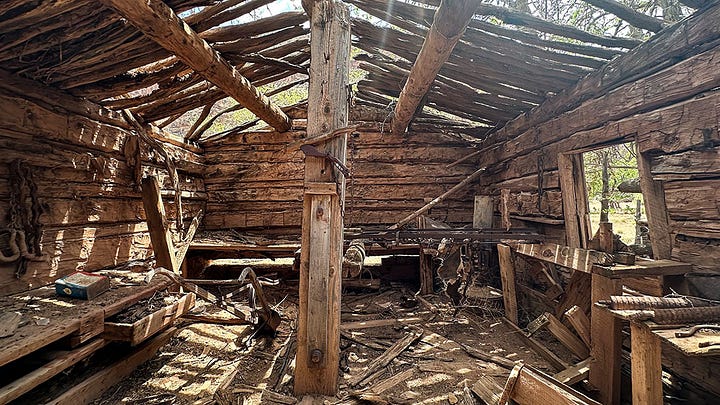

We ran some modest rapids that day, the first since launch, although Scotty took dry lines through them because it was still cold and we were not eager to get soaked. We stopped at Rock Creek, a clear-running anomaly in the watershed of a sediment-laden river, to hike to a spectacular Fremont petroglyph panel. We stopped for lunch just downstream at the site of the historic Rock Creek Ranch, where we toured the crumbling remnants of a stone cabin and wooden workshop. The afternoon warmed up, and with it our spirits, and after 13 miles of river we pulled into a lovely campsite.

And so it went, day by day, until we came to the end. The second half of the trip was markedly warmer than the first half, and so we welcomed the splash of the more numerous and sporty rapids. As the miles passed, the great red walls of Desolation Canyon’s sandstone fell back from the river and gave way to the much less spectacular geology and more open countryside of Gray Canyon, which encloses the final 24 miles of the river before the takeout at Swasey’s boat ramp.

There were more hikes during those final three days, and a “lunchover day” when we pulled into a fine picnic spot that would also be our camp for the night. This allowed us all an idle afternoon to relax in the shade, drink beer, tell tales of river trips past, listen to the river’s liquid song, and watch clouds and driftwood float by.

And that gets to the heart of what made this trip so different from all that had come before. Even a conventional commercial trip has its version of river time, but that is tempered somewhat by the logistical and interpersonal complexities introduced by a dozen or more guests and an expanded roster of guides. The basic work of rowing, setting up camp and preparing meals is largely the same on a bigger trip, but add to that the task of unloading a dozen or more extra dry bags and sleeping pads; the jockeying of guests rushing to grab gear and stake out prime tent spots upon landing at camp; the after-breakfast line for the groover (river lingo for the portable camp toilet); the inevitable stragglers late to the beach with tent and gear for the morning loading; and what you have is a far less relaxed and intimate experience than our six days with Scotty, Nikki, Rose and Emily.

Not a bad one, not at all. Just very different. And we now have been spoiled.

At the takeout, Leslie and I helped the crew empty and de-rig the rafts, and load the components of our floating village onto the ARTA truck. It’s always hard to part from people with whom you have shared such an intense experience, especially when they have been responsible also for keeping you safe, well-fed and entertained, but this time it was particularly poignant. We could not have asked for better companions during our adventure on one of the great rivers of the West, and I still am missing our new friends. When the loading was about done, we said our emotional goodbyes to Nikki, Rose and Emily, and climbed into an ARTA van with Scotty for the short drive back to our hotel in Green River.

After nearly a week under a wide vault of sky, uncluttered by anything but the spring-leafed crowns of ancient cottonwoods, the interior of the van felt claustrophobically cramped. And after days riding on the back of a wandering 4-mph waterway, the experience of sudden motorized acceleration and speed along the paved road to town felt almost like flying.

But although the van carried us back to civilization, it could not take us away from the river. That liquid song lives in us still.

My favorite line among many favorites: “While we were doing so Uncle Gusty showed up with all his cousins, nieces, nephews and friends, bearing lightning, thunder, rain and hail — skin-stinging horizontal hail, driven by a sudden microburst that blasted through the canyon.” Ruskin called it the pathetic fallacy, which seems cruel for writing so vivid. Great tale, John.

Hi John! Loved your tales of your river rafting trip. And as Tim said, the Uncle Gusty and his relatives was an excellent way to tell that tale! We have been on three rafting trips for the past 3 years. We love those experiences, however, like you said being the only guests meant no paddling unless you did the kayaks. Loved your pictures of a beautiful river. Have you been on the Yampa? It's has an amazing backdrop. Well can't wait for your next trip!! Jill