Thirteen Days of Serendipity

Mechanical calamity triggers an enjoyable digression

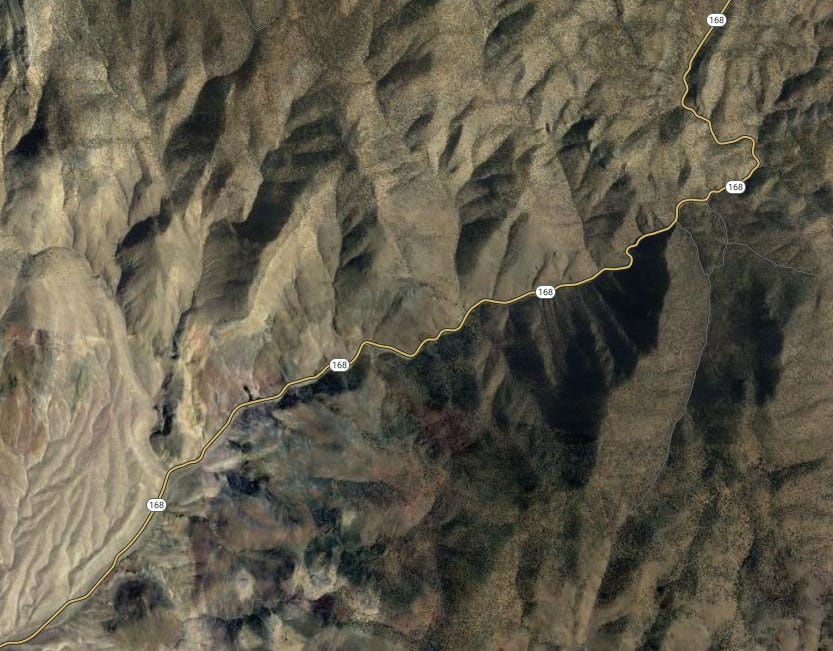

Highway 168 in the White Mountains of eastern California is perhaps the worst place in the world for the power steering on your camper van to fail.

The highway is 12 miles of narrow, vertiginous hairpin curves as it climbs from the Owens Valley at Big Pine to the Ancient Bristlecone Pine Forest, gaining more than 5,000 feet in elevation. In many stretches it is a single lane wide, and more than a few of the nonstop curves are blind.

So of course that’s where our steering broke down last month in Next Chapter.

It was the first day of a meticulously planned three-week road trip in September, designed so we could enjoy autumn weather in the Wind River range of Wyoming, the High Uintas of Utah, and the Ruby Mountains of Nevada. We intended to spend our first night of the trip in the Inyo National Forest’s aptly named Grandview Campground, at nearly 9,000 feet in the White Mountains not far from the Inyo’s bristlecone visitor center.

We had just begun the most tortuous part of the drive up the 168 when the system failed. One minute the van was behaving normally, and the next the steering wheel practically froze. My partner Leslie was driving, and suddenly found she could barely crank the wheels far enough to navigate the road’s sharp corners, straining with the effort. There was no place to pull over, let alone turn around, so we continued up the mountain at a crawl, praying not to meet oncoming traffic.

Fortunately, we did not. We limped into the campground and found a site for the night, though not without struggle. We found that when the van was at a standstill, it was impossible to turn the wheels — only when it was moving could we wrench the steering wheel in either direction — which made it very challenging to navigate tight spots in the primitive campground.

Once we parked and were able to inspect the van, we found the front undercarriage drenched in some kind of oily liquid — presumably the power steering system’s hydraulic fluid, likely leaking from a blown seal or perforated hose. We set up camp, settled our jangled nerves with a cocktail, and pondered our options.

We did not have many. There is no cell service in the White Mountains, and even if we’d been able to contact AAA roadside assistance, it seems unlikely they could have persuaded a towing service to come fetch our rig up there. We concluded we would have to drive out the next day, and search for a mechanic once we had cell service again.

Needless to say, we did not sleep well that night. In the morning, we packed up camp and I piloted the van back down the mountain. In addition to the tight curves and narrow lanes, the steep downhill grade meant that I was simultaneously fighting with the recalcitrant steering wheel and pumping the brakes to keep from losing control and drifting off the shoulder into an abyss. It was the most terrifying drive of my life.

Fortunately, we made it back to flatland without incident. The nearest town was Big Pine, a hamlet scant on services, so we headed north on Highway 395 toward Bishop, the largest town in the Owens Valley. Thankfully, it wasn’t too difficult to drive the van at highway speed in more or less a straight line, although I stayed well below the 65 mph speed limit.

As I drove, Leslie began calling mechanics to determine our odds of repair. It was a Friday, which meant we were already facing a tight window before businesses closed up for the weekend, and a Mercedes Sprinter is a fairly exotic beast, meaning there was little chance we would find a specialist there and an even smaller chance that a Bishop repair shop would have whatever parts we needed in stock.

Sure enough, no one was able to take us in on short notice. Facing the prospect of a lengthy layover in Bishop while we waited for help that might never materialize, we turned around instead and began the 300-mile drive back to Ventura, so we could drop Next Chapter with our local Mercedes service center and have it tended to by trusted experts. We arrived back at home late Friday, and left the van at the shop in Oxnard the next morning.

The immediate diagnosis was that a pressure hose in the power steering system had ruptured. The replacement part was ordered on Monday, and installed on Tuesday. We got the van back on Wednesday, and prepared to resume our aborted adventure. By now, however, we had lost a week, and could not make it to Wyoming and back in the time we had left before non-travel commitments loomed on our calendar.

So we shifted to Plan B. Which was not so much a plan as a vague assortment of general destinations we hoped to explore closer to home. I pulled a stack of national forest maps out of the file cabinet and started jotting down some ideas. So began our Sierra Nevada Serendipity Tour.

West-slope byways

A week after our ill-fated initial launch, we were back on the road, headed north through the Central Valley. We got a late start, having had to pack all over again, so aimed modestly for a Hipcamp site I’d rented about three hours away on a small walnut farm.

Our general idea was to work our way up the Western slope of the Sierra, periodically making forays up the roads that cross the mountains, eventually following one over a summit pass and down into the valleys at the eastern foot of the range, where we would repeat the pattern as we worked our way south. We have done versions of this itinerary several times, but the emphasis this time was on exploring new areas, taking roads we’d never traveled before, camping in unfamiliar places.

The next morning, we headed up into the Sierra foothills toward Shaver Lake, intending to make our way into the Sierra National Forest and camp near a trailhead into the Dinkey Lakes Wilderness so we could go hiking. Storms earlier this year had blown out some of the unpaved roads in the area, so we stopped first at the forest headquarters for an update on conditions and camping options.

The news was mixed. The trailhead was accessible despite some road closures, the woman at the information desk told us, but our plans for dispersed camping in the area were ill-timed: The next day was the opening of deer season, and hunters had been heading into the forest all day to stake out base camps for the weekend. So had off-road vehicle enthusiasts, drawn by some kind of annual rally.

“I’ve seen them going by all day on the highway hauling their rock-hoppers up there,” she said.

So, not only would the dispersed camping areas be overrun, they would be overrun by people shooting guns and/or roaring around on loud vehicles — not a setting conducive to finding the peace and relaxation we sought.

“That’s why I don’t go into the forest,” she said.

It was an odd remark for someone affiliated with management of that forest, but we shared her aversion to crowds and noise. So we turned back, picked up Highway 49 through Mother Lode country, and headed north to Highway 120, western gateway to Yosemite. A few miles along, near the town of Groveland — world headquarters for ARTA, our favorite whitewater rafting company — we peeled off onto a dirt road into the Stanislaus National Forest and found a suitable boondocking site. It was not a great site, but it was late and it was a Friday night. Our standards tend to loosen under such conditions.

We resumed our journey the next day. We drove for a couple hours up Highway 108 deeper into the Stanislaus, and found a dispersed camping spot two miles down a dirt road on the edge of a small meadow filled with wildflowers. It was a magical spot, alive with butterflies and bumblebees and other wild pollinators, periodically visited by chattering clouds of small birds, and we camped there for two nights. The layover gave us time to read, take long walks in a lovely woodland, and just watch wordlessly as the changing angle of the sun throughout the day created a kaleidoscopic interplay of shadow and light in the treetops.

After drinking our fill of the setting, we drove farther east to a nearly empty developed campground on the Clark Fork of the Stanislaus River and camped there another two nights, giving us time to hike, make pictures and fish along the beautiful stream.

Short drives and leisurely camp days are travel goals Leslie and I often talk about but have not been very good at achieving. Apparently, it took a mechanical calamity to force a trip recalibration that allowed us finally to do so.

From the Clark Fork, we headed for the destination on this improvisational itinerary I most wanted to explore: Silver Lake, a small and scenic water body in the High Sierra off Highway 88 just south of Lake Tahoe. As I have written about before, it was the first place my parents camped together, when they were young newlyweds, and it was the first place they took me camping, when I was a toddler. I have only vague memories of it, and had not revisited it since our family stopped going there in my childhood, shifting our allegiance instead to the incomparable Warner Valley in Lassen Volcanic National Park.

Fishing in the past

We rolled into the Silver Lake East campground in the afternoon as shadows were lengthening and travelers were beginning to pull off the highway in search of a place to spend the night. Because it was late in the season, the U.S. Forest Service had closed most of the campground to concentrate use (and its maintenance obligations) in a single loop of campsites. One the other side of the highway, the El Dorado Irrigation District, which manages the lake for irrigation and hydropower, had closed its Silver Lake West campground entirely.

This was greatly disappointing, because I believe that’s the area my family would have camped in the late 1950s and early 1960s. The Silver Fork of the American River flows along the edge of the campground, and stream fishing was my dad’s favorite pastime in those days, so it is logical that they would have chosen that area to camp. That makes it likely the place he and I first fished together when I was a kid.

We found a suitable site in the open campground and settled in. The next morning, we went exploring. We walked across the highway and into the Silver Lake West campground, ignoring the “Closed” signs, and made our way to the edge of the river.

I don’t know what I expected. After 60 years, I have so little direct memory of the place that it did not look familiar and conjured no immediate emotional response. Instead, what struck me was just how staggeringly beautiful it is.

The river tumbles through the forest down a spectacular staircase of polished granite, before leveling and flowing briskly past thick stands of white firs and Jeffrey pines, and I could imagine how it would have drawn my trout-seeking dad like a magnet. I could imagine, too, how it must have felt like a magical realm to my young parents, because I also was young once and in love, and drawn powerfully to such lush, romantic landscapes.

Now I am old and in love, and still drawn to them. I sensed for a time that morning that my parents were present, their spritely young spirits lingering there in the deep forest shade to watch the sparkle of sunlight dancing across the living water and revel in the piping song of small birds in the trees.

East-slope byways

From Silver Lake we headed east on Highway 88, and over the Sierra crest at Carson Pass. At the foot of the mountains we hooked up with Highway 395, but instead of following it south along the eastern front of the Sierra as we typically have, we detoured a few miles later into Nevada along Highways 208 and 338, new territory for us. They led us into a land of sagebrush steppe flanked by snow-dappled mountains, and eventually to a dirt road that we followed for more than 5 miles to a camp on the bank of the East Walker River.

The Walker River and its tributaries drain off the eastern Sierra into a basin with no outlet, occupied by terminal Walker Lake. Once supporting a robust ecosystem, including a rich native fishery and the indigenous Paiute tribal peoples, the lake has been driven into ecological collapse by more than a century of water diversions in the service of a marginal cattle ranching economy.

The spot where we camped is a relatively new Nevada state park unit made possible by the Walker Basin Conservancy, established in 2015 to acquire land and water rights to restore the lake’s ecological health. The Conservancy donated thousands of acres of land and more than 30 miles of river, most acquired from old ranching operations, to the state as the nucleus of the Walker River State Recreation Area.

This is how we found ourselves in the middle of nowhere staying in the quite improbable Bighorn Basin Campground, complete with clean restrooms, picnic tables and fire rings. Developed five years ago, it’s located on a big bend in the river called The Elbow, and is clearly popular with anglers drawn by the East Walker’s legendary lunker trout population. It’s also popular with cows, judging by the density of fresh dung deposits.

It was 25 degrees at sunrise the next morning, a tangible reminder that the season had changed, and we lit our propane fire pit to warm us while we enjoyed our morning coffee. As we sipped, we kept a lookout for members of the resident bighorn sheep herd high on the steep ridge above the river, but they were no-shows.

Once we were back on the road, we headed south to Bridgeport and resumed our journey down Highway 395, stopping for the night at a campground on Lee Vining Creek, just off the Tioga Pass Road to the Yosemite high county. The next day, we detoured onto Highway 120 East and overnighted in a pumice-floored boondocker site in the Inyo National Forest, just a few miles from the volcanic Mono Craters, which had paved it with their ashy exhalations.

In the morning we resumed our journey, through countryside new to us. As we followed the long, narrow reach of highway curving across the dry landscape we passed shallow lakes, granite peaks, a deep gorge, and mile after mile of brilliant yellow rabbitbrush, which blooms in fall and filled the air with a heady perfume.

Just past the historic little town of Benton Hot Springs, Highway 120 meets Highway 6, which we followed south along the foot of the White Mountains to Bishop, where we rejoined Highway 395. Our last two nights on the road were spent off the 395, camped along creeks that descend through canyons etched into the eastern Sierra front.

One site was on Bishop Creek, in a campground where we have stayed before, but the final one was on Independence Creek, which was new to us. Our site there featured a private sand beach, where we toasted the final lavender sunset of our unplanned — but thoroughly enjoyable — autumn journey.

Beautiful writing and beautiful photos, John! So glad you made it home (and away from home) safely!

I’ve just taken an enjoyable adventure with you to vicariously. The photos are fabulous.