It was a hot day in August when we pulled our van to the side of a decrepit country road, winding along the shoreline of a small lake on the Oregon-California border, to take in the view.

Although a sign nearby advertised a hill-top housing development called “Iron Gate Lake Estates,” our vista was not of open water. Instead we looked out over a shallow valley, its gray-and-tan terrain sprinkled with sparse patches of vegetation and cloven by the winding Klamath River.

Although it sparkled in the smoke-hazy sunshine, the Klamath looked odd, murky and nearly black instead of its typical blue-green. Although a silty hue is normal for sediment-laden rivers in the scantily vegetated desert Southwest, it is unusual for a Pacific Northwest river like the Klamath, which traces its headwaters to the evergreen-forested flanks of Mt. Mazama, the ancient Cascade Range volcano that’s the centerpiece of Crater Lake National Park.

But water color was not the most unusual aspect of the scene. Less than a year earlier, the largely barren valley my partner Leslie and I could see that day from our Next Chapter adventure van was not occupied by a river at all. It was filled by a 944-acre lake impounded by Iron Gate Dam, an earthen embankment 173 feet tall and 741 feet wide, placed there more than 60 years ago to generate hydroelectric power.

We visited the site of the vanished reservoir during a two-week trip this summer that took us across most of the Klamath River’s 16,000-square-mile watershed, from the mountains to the sea, from high sagebrush desert to moist redwood cathedral, from a landscape of agriculture and contention to one of restoration and hope.

I’d first visited this landscape 20 years ago, as a newspaper reporter working on a series of stories about conflicts over water resources in the West. My journey then to the Klamath Basin was drawn by a tectonic collision of demands on the Klamath River system, one that involved a scrum of competing interests — white farmers dependent on federally subsidized irrigation, indigenous tribal members trying to preserve traditional foodways, commercial fishers on the Pacific Coast, wildlife managers responsible for imperiled waterfowl habitat, environmentalists defending endangered species — and had escalated to the point of violent confrontations and gunfire.

Our journey this summer was driven by something decidedly more positive: a chance to visit the site of the largest dam-removal project in American history, one that could revive an ancient and sacred relationship between the people who have called the Klamath watershed home for millennia and the fish that have long been at the heart of their world.

Four hours in Medford

We spent the first three days of our summer journey on the road, aiming for an area along the Upper Rogue River in Oregon where we had spent a couple of blissful days last summer. The third day, however, nearly ended our trip before it had really begun.

We were just leaving California, following Interstate 5 north toward Oregon and beginning the long and rather steep ascent toward 4,310-foot Siskiyou Mountain Summit, when the van suddenly lost power. Leslie was driving, and although she had the accelerator floored, we steadily lost speed until we were creeping uphill at about 30 mph, tangled up in a lumbering stream of 18-wheelers.

She pulled off at the next exit while we pondered our options. Clearly, we needed to get to a repair shop, but we already knew there was no significant town or city to the south of us for more than 100 miles. Consulting a map, we calculated that Medford, Ore., was only about 20 miles to the north.

So Leslie pulled us back onto I-5, and resumed the long, unnerving ascent while I waited for a cell signal so I could research repair options in town. In a minor miracle, Medford turned out to have a Mercedes-Benz dealership with a service department that specializes in Sprinter vans, a fairly unusual occurrence. We crept over the summit, and basically coasted downhill through Ashland and on to Medford. I called the shop to let them know we were coming, and was told that they were backed up with work already but would see what they could do.

When we arrived, we handed over the keys and walked to a nearby pizza place for lunch. When we returned, service advisor Dan Wolf said the mechanic had discovered the cause of our power loss: A failed seal had crippled the turbocharger unit, without which a Sprinter apparently has all the git-up-and-go of a banana slug. He said they could replace the seal, replenish lost engine oil, and have us back on the road in a couple hours.

The crew was as good as their word, another minor miracle. Four hours after we limped into Mercedes of Medford we were back on the highway and headed for the Upper Rogue. As I’ve said before, when you’re on the road, luck is sometimes more important than good planning.

Camping with fire

Without further drama, we made our way to the same boondocking site near the Rogue that we used in 2023. We set up camp in a smoky forest of Douglas firs and enjoyed a well-deserved cocktail, toasting the good fortune that made it possible for us to be there after a very long and trying day

We were awakened in the middle of the night by the unexpected sound of raindrops on the van’s roof. Since our camp kitchen was set up outside and unprotected, owing to the lack of rainfall in the local weather forecast, we tumbled out into the warm darkness to unfurl the van’s awning over our outdoor living space.

The next morning was drizzly, warm, humid and smoky, an odd combination of atmospheric phenomena. Nevertheless we pulled on daypacks and headed down the nearby dirt road toward a trailhead about a mile away, at the former site of a developed U.S. Forest Service campground right on the river bank. We were surprised to find it empty — a year earlier it had been busy with campers and anglers — so we hurried back to camp, packed up and relocated to the far superior place. We had it to ourselves the next two nights.

At one time there were picnic tables, restrooms and a potable-water pump in the 10-site campground, along with sturdy fireplaces. The USFS decommissioned the campground more than a decade ago, however, removing all the improvements except the fireplaces, which were over-engineered out of mortar and native rock in a style that suggests they almost certainly are a 1930s legacy of the Civilian Conservation Corps, which built hundreds of campgrounds in national forests and national parks during the Great Depression.

We may have been alone there, which is how we prefer our camp sites, but we were not left in quiet solitude. Low-flying helicopters were circling the area, raising an alarming cacophony and posing a mystery about their purpose. We were able to solve it by hiking a short distance to a footbridge across the Rogue. In a meadow there, at the trailhead for a path along the river, we came across a support team that had installed a pump and a hose line to move river water into what looked like an above-ground swimming pool. The helicopters were taking turns dipping buckets and snorkels into the pool, slurping up hundreds of gallons of Rogue River at a time and flying over the adjacent ridge to drop it onto a wildfire in Crater Lake National Park, which accounted for the generally smoky air in our corner of the forest.

The unexpected entertainment was welcome, and I was able to capture some of it on video, but we did not miss it when it stopped. Instead of enduring the thwap of rotors we could enjoy the music of chestnut-backed chickadees.

Our final day there dawned under a hazy blue sky, so we hiked the river “trail,” such as it was. There clearly had been no human maintenance of it in years, although grazing cows had added their own improvements, which mostly consisted of a confusing maze of hoofpaths that obscured the real trail and led through dense underbrush into vegetative dead-ends along the river bank. Plus, bovine trail crews shit all over their handiwork, unlike their human counterparts, so there were other obstacles to avoid.

Nevertheless, our 2-mile trek was enjoyable once we found the overgrown old footbed, despite the deadfall that slowed us to a crawl. We had a picnic lunch close enough to the river to hear its voice, if not near enough to see it, and the day grew clear and warm and quieter, dwindling helicopter traffic suggesting that the unforeseen rain had aided in fire suppression. At last we enjoyed the silence of the forest, which is not silence at all but a subtle symphony of birdsong, riversong, windsong, treesong that requires mindfulness to hear.

Reviving a river

From the Upper Rogue we headed to Upper Klamath Lake. It is the largest lake by surface area in Oregon, although it is quite shallow, averaging only 8 feet in depth. It’s the dominant topographic feature in the Upper Klamath Basin, which straddles the California-Oregon border, and we had booked two nights on its western shoreline at the very rustic Rocky Point Resort.

Despite its time-worn condition, I have fond memories of the resort from my reporting trip in 2003. I stayed there (along with a photographer colleague) while traveling around the Klamath Basin, interviewing people about their struggles over water. Although the situation I reported on was complicated, it basically boiled down to too many demands on a limited resource — a situation common to nearly every watershed in the West.

At the heart of the story was the vast reworking of the basin’s natural plumbing system in the early 1900s by the federal government, which drained lakes and wetlands so they could be farmed, and deployed dams and canals to divert most of the natural flow in the Klamath River and its tributaries to irrigate those farms. It turned the semi-arid basin into an improbable agricultural powerhouse, funneling copious runoff from the mountains that surround it into fields of alfalfa, potatoes, mint, grain and onions.

Although it was a boon for white homesteaders, the Klamath Project was a disaster for waterfowl, fish species — notably salmon and two species of suckers, all of which have ended up on the endangered species list — and for the indigenous people who had for centuries relied on that natural bounty for sustenance. Those tensions boiled over in 2001 when the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation shut off water deliveries to farmers during an intense drought in order to maintain river flows for imperiled fish. Protests and violent encounters broke out. Lawsuits followed.

The USBR’s Klamath Project was not the only insult the early 20th century visited upon the Klamath River and its watershed. Downstream from Upper Klamath Lake, just over the California border, a regional power company built seven hydroelectric dams between 1918 and 1962. Like the irrigation dam at the lower end of Upper Klamath Lake, the hydro dams (later acquired by PacifiCorp) prevented the Klamath’s chinook and coho salmon from accessing their ancestral spawning grounds in hundreds of miles of tributary streams.

Those spawning grounds play a critical role in the life cycle of Pacific salmon. Hatched from eggs in those cold, clear streams, they spend a few months or even a year there (depending on species) before heading downstream to the main stem of the Klamath and then out to sea. They spend a few years grazing in pelagic pastures and growing large before returning to fresh water and battling their way back to their natal streams to mate, spawn and die.

Blocked by dams, they end up trying to spawn in vastly inferior locations. The impounded reservoir waters warm up during the hot summer months, reaching levels that can be lethal for salmon and other aquatic species downstream when that water passes through the generating plants. Additionally, shallow Upper Klamath Lake is plagued by toxic algae blooms, adding another danger for fish in the river when the USBR releases water to maintain flows thought necessary for their survival. The decline of the Klamath River’s iconic salmon population — once the third-largest in the West, now reduced by more than 90 percent — is proof of the biological truism that fish don’t just need water to thrive, they need the right kind of water.

Much has changed, however, in the two decades since my previous visit to the Klamath Basin. In the area of the Klamath Irrigation Project, for example, the Department of Interior (bureaucratic home of the USBR) earlier this year announced a comprehensive agreement among native tribes, project irrigators, and state and federal agencies — the parties that were caught up in bitter strife back in 2001 — to collaborate on what it describes as “the Klamath Basin Drought Resilience Keystone Initiative, a new effort to steward investments from President Biden’s Bipartisan Infrastructure Law and Inflation Reduction Act, and support a wide range of restoration activities that will help recover listed species, create new habitat for fish and birds, and rethink the way water moves across the Klamath Basin to better align agriculture with ecosystem function.”

The restoration agreement (and millions of dollars in funding) comes at the same time that PacifiCorp, having determined that it could not afford to upgrade its hydropower dams to meet current legal standards — which would have been required if it had applied to renew their licenses from the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission — instead handed them over to the nonprofit Klamath River Renewal Corp., which is in the process of removing four of them: Iron Gate, Copco 1, Copco 2 and JC Boyle.

Copco 2 is already gone; the other three will be by the end of this year. All their reservoirs have been drained, and the Klamath River is allowed to pass freely again along 38 miles of its formerly drowned bed, carving a new course and sluicing accumulated sediment downstream. The KRRC will also manage a vast ecological restoration effort aimed at transforming the barren former reservoir sites and 400 miles of tributary streams, reopened to salmon for the first time in more than a century, into vibrant native habitat.

Erosion of reservoir sediment accounted for the murky color of the river when we visited the Iron Gate Dam project area after our stay at Rocky Point. From the former shore of Iron Gate Lake, we could see excavators re-contouring slopes and huge dump trucks in the distance carting away the earthen fill of the dam itself, which is being deposited on site in the borrow pit from which it was removed to create the dam in 1962.

The dam removal is the culmination of decades of work by river advocates, including several native tribes of the Klamath watershed (notably the Klamath, Modoc and Kahooskin in the Upper Klamath Basin, and the Yurok, Karuk, Hoopa and Shasta in the Lower Basin). The project, like the new collaborative initiatives seeking a better balance between farmers’ needs, native rights and ecosystem health, represents a remarkably hopeful development. If you’d asked me 20 years ago whether I thought such a day would ever come, I likely would have said no. The conflict seemed too entrenched, the bitterness too acute.

From Iron Gate, we returned to Interstate 5 and began our trek to the other end of the Klamath River. Our destination that day was the small town of Klamath, on the Northern California coast where the river ends its 257-mile journey to the sea.

After leaving Iron Gate Dam, the river itself carves a deep canyon through the rugged Klamath and Siskiyou mountains, and although it is possible to follow it quite some distance on a narrow, twisting road, the Coast Range eventually proves an insurmountable barrier and that highway dead-ends well short of the Pacific.

Rather than follow the river and then make a very long detour, we’d decided that our most expeditious course to Klamath was to take I-5 north to Grants Pass, Ore., and then follow Highway 199 through the Coast Range, and the stately groves of Redwood National and State Parks, to Crescent City, Calif. From there, Highway 101 would deliver us swiftly to Klamath and the river’s mouth.

The drive was long, but it was scenic and our second ascent of Siskiyou Summit was far less dramatic than the first. We reached Klamath early that evening and checked into our room at the Historic Requa Inn, built in 1914 and all that remains of the town of Requa, once the largest community in the Klamath region and home to several commercial salmon canneries in the early 20th century. Its name comes from the Yurok name for the indigenous village that long predated the first white settlement in the area: Re’kwoi, meaning “mouth of the creek.”

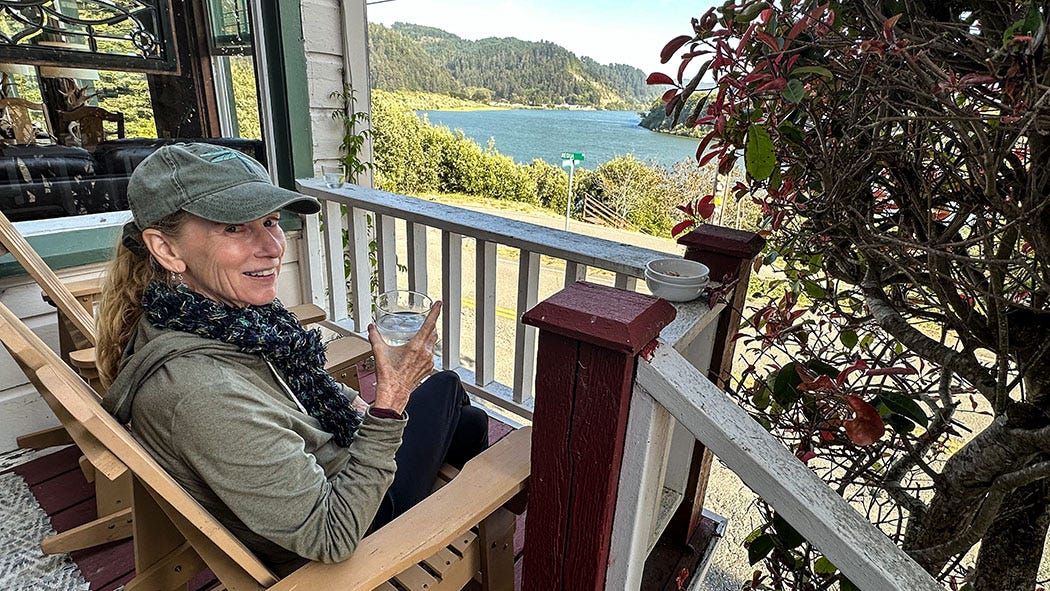

The inn is perched along the Klamath River on a low ridge, which is why it survived the epic flooding in December 1964 that destroyed the rest of Requa as well as the nearby town of Klamath and many other communities in Northern California and Oregon. We enjoyed a cocktail on our room’s small deck, which overlooked the river’s blue-green water, so different from the turbid, coffee-colored flow we’d encountered earlier that day.

The next afternoon produced the highlight of our Klamath journey.

Sacred fish

After a hearty breakfast in the Requa Inn’s dining room, we made our way to the Yurok Country Visitor Center in downtown Klamath. Exhibits there focused on the region’s history, as well as the Yuroks’ effort to revive their language and cultural traditions after decades of dispossession, suppression and violence.

The Yurok are a river people, and they are also a salmon people, linked to indigenous groups along the entire length of the Klamath and its tributaries by their shared intimacy with the remarkable life journey of an iconic fish. For the river people of the Pacific Northwest, salmon traditionally played a dominant role in sustenance and spiritual belief similar to the role of bison among the indigenous people of the Great Plains.

Logging, mining and rapacious exploitation by commercial fishers and cannery fleets dealt serious blows to salmon populations across the West in the early 20th century, but it was the proliferation of dams blocking off hundreds of miles of tributary streams that spelled doom for the Klamath River’s once-bountiful runs of chinook and coho. And as salmon dwindled, the Yurok and the other river tribes lost a foundational element of their culture and economy.

But perhaps there’s a new reason for hope, thanks mainly to the restorative events now transpiring some 300 miles upstream. The Yurok certainly think so. Leslie and I learned a bit about their hopes and dreams and reclaimed cultural legacy during a two-hour paddling voyage along the Klamath River with a tribal guide in a 20-foot hand-carved canoe.

Such canoes, each artfully hewn from a single redwood log, were once common on the river. In the era before roads, the most efficient way to transport people and goods through the dense coastal forest was by water, and watercraft were also essential to setting nets and weirs to catch fish. It took many years of apprenticeship to become a master canoe carver, and with the arrival of aluminum skiffs with outboard motors — plus the gradual erosion of indigenous cultural traditions and rituals under assimilative pressure during the late 19th and early 20th centuries — the craft was nearly lost. And during the 1964 floods, nearly all of the surviving canoes built by previous generations (if properly cared for they can last a century) were washed away.

The craft of canoe carving has been revived, however, thanks to a few elders who still knew the old techniques and a new generation intent on perpetuating them. The tribe now has about a dozen traditionally crafted redwood canoes, and a few years ago, the Yurok launched a commercial tour business, welcoming paying guests to spend time in these remarkable creations while learning about Yurok history and culture from tribal members themselves.

We caravanned with our tour guides from the visitor center to the launch site a few miles upriver, and then clambered into the canoes and pushed off. In our party were four guides and six guests in two canoes; ours headed downstream under the command of captain Gus, while the other headed upstream under the guidance of captain Kobe.

Unlike most river trips we take, Leslie and I were passive passengers while Gus and his bow paddler did all the work. And for the next two hours, Gus continuously narrated our tour, recounting tribal history and legends, describing such episodes as the “fish wars” of the 1970s and the landmark U.S Supreme Court decision that restored the Yuroks’ sovereignty and Klamath River fishing rights after the state and federal governments had attempted to extinguish both. He told of the annual “first fish” ceremony, held when each salmon run began at the coast, and of how a messenger was sent from each village to the next one upstream to spread word that the time to set nets and weirs was drawing near.

He also described the important role the tribe is playing in the ecological restoration of the PacifiCorp dam sites just below Upper Klamath Lake, tribal members having designed and begun to implement the massive revegetation project for the temporarily barren reservoir sites. The work includes collecting and sowing billions of native plant seeds, and planting thousands of trees and shrubs, and is integral to the restoration project that the Yurok hope will help Klamath salmon recover.

Gus also spoke of the significance of the canoe itself, which is unlike any of the many types of watercraft I have paddled or ridden on western rivers. It was easily the least comfortable perch I have ever occupied in a boat — seating consisted of hourglass-shaped wooden stools that were unattached to the canoe and placed a passenger’s center of gravity awkwardly high above the shallow craft’s low sides. The canoe itself is extremely stable but the perch felt precarious and my butt was aching after the first 30 minutes.

But it was more than worth the discomfort to feel a deep sense of connection to the river and to a thousand years of indigenous occupation of this land of water and fish and towering redwoods. The Yurok believe the canoe, like everything else in their world, is alive and has its own spirit — one that is a composite, Gus said, of the spirits of everyone who helped create it. As befits a living being, the canoe builders carve symbolic features representing lungs, a heart and kidneys into the redwood, as well as a lifeline that encircles the entire craft.

“We believe that when a redwood tree falls, it decides what it wants to be in its next life,” Gus said. If it falls and remains intact, he explained, that means it wants to be a canoe. It if falls and shatters, it wants to be carved into paddles or household items. If it falls and breaks into large slabs, it wants to become a Yurok plank house.

So we found ourselves borne on the back of a living thing that had towered in a misty forest for centuries before falling to earth with the wish that it become a floating work of craft, art and spirit. We saw ospreys wheel and keen in a blue sky, and heard the rhythmic splash of paddles stir the bright water of a once-great river that may one day be restored.

This was not the end of our trip, of course. Over the next four days we would travel many more miles of coastal highway on our long trek home. We would hike in the redwoods south of Klamath, visit a botanical garden in Fort Bragg, camp in a forest outside of Mendocino, explore a national seashore and indulge ourselves with a luxurious hotel stay at Nick’s Cove on Tomales Bay. These were all wonderful experiences, too.

But it is the memory of that afternoon in the redwood canoe — when the lines between past, present and future blurred, when “what was” and “what could be” merged into one story — that has lingered longest since we returned home.

Another stellar installment John.

The ‘River People’ along the Washington, Oregon and NorCal coastline have such an incredible story to tell. Thank you for sharing your insights into that historic narrative!

And thank you Leslie for the great photography.

Cheers,

Doug

I am spending some holiday downtime catching up on Next Chapter, starting with the most recent first. This one is a beautiful read - thank you.