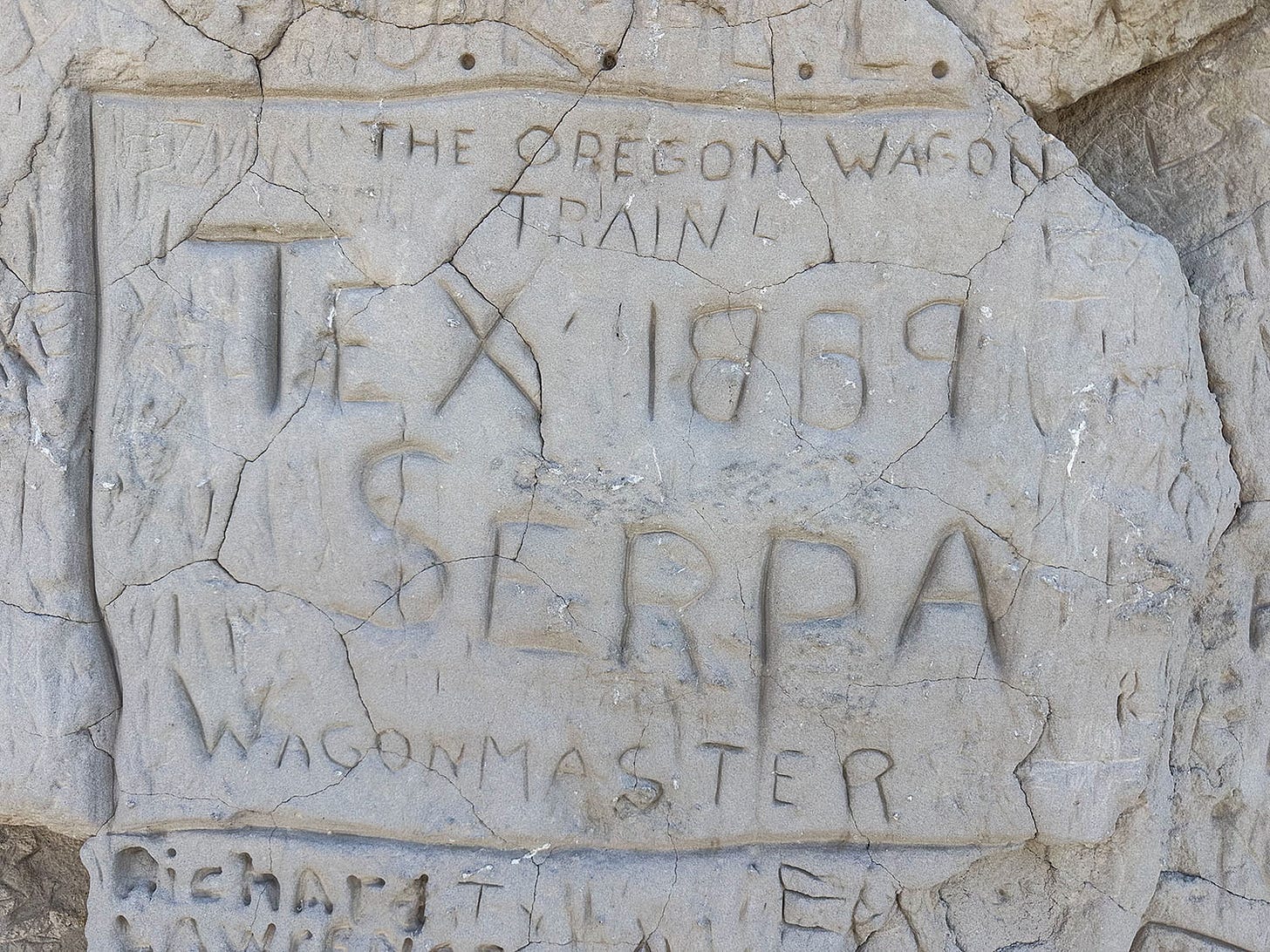

In Part 4 of my recently concluded series about our travels on the Santa Fe and Oregon Trails this spring (“The Great Platte River Road”), I recounted our visit to Register Cliff State Historic Site. Located on the bank of the North Platte River in Wyoming, it preserves a popular Oregon Trail emigrant camp site where travelers carved their names into the soft sandstone of a prominent ridge. And I posted this photo with it, assuming the inscription — appearing to be among the best-preserved at the site — was an authentic 19th century tag.

Turns out, not so much. So to set the record straight — and because the ensuing bout of sleuthing is entertaining — here’s some bonus content.

A friend, E.J. Remson, passed my piece along to a co-worker whose last name is Serpa, who did some digging and came up with the following online post:

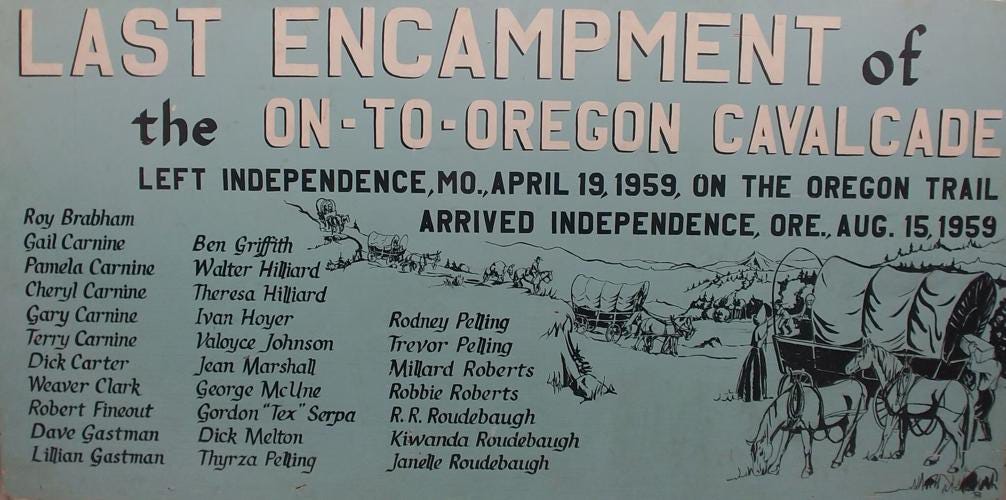

"My name is Scott Serpa. I just ran across your blog and thought I would clear up a little history for you. Gordon “Tex” Serpa was my father. In 1959 Oregon celebrated its 100th birthday. A group calling themselves “The On To Oregon Cavalcade,” led by my father, reenacted the historic path of the pioneers by traveling by horse drawn wagon train from Independence Missouri to Independence Oregon. The carving my father made on the rock was originally dated 1959 only to be vandalized to read 1859 and then 1889.”

There is plenty of modern graffiti marring historic and prehistoric registers across the West, and there is an interesting debate to be had about how old a name scratched, pecked or painted onto a rock must be before it can be regarded as art or culturally symbolic expression instead of vandalism.

But the tale about Tex is true. After I heard from my friend (Thanks, E.J., for passing that along!) I did some digging of my own. What follows are two newspaper stories about the 1959 cavalcade, one contemporaneous with it and likely the most accurate — United Press International (UPI), one of the leading newspaper wire services back in the day, was always a sober stickler for accuracy — the other more recent and its divergent details perhaps reflecting how history blurs in the memory of its living repositories.

Oregon Centennial Features Wagon Train

(Published April 9, 1959, in the Madera (Calif.) Daily News-Tribune, retrieved from the California Digital Newspaper Collection, Center for Bibliographic Studies and Research, University of California, Riverside)

By James Doyle

PORTLAND (UPI) — The crack of a bull whip, a cowboy yell and six lumbering Conestoga wagons will rumble onto the Oregon Trail and head for the Northwest.

This action April 19 will follow a brief ceremony at Independence, Mo., in which former President Truman will receive a lesson in bull whipping from a modern day wagon master — Gordon (Tex) Serpa, 39, Ashland, Ore.

Amid cheers and good wishes, 25 persons will man the wagons and start a 2,000-mile, 130-day reenactment of the Oregon Trail blazing.

The wagons will make up the “On to Oregon Cavalcade” in honor of the 100th birthday of Oregon.

Serpa will take charge with the same military-like authority that the pioneers found necessary.

“We expect many hardships on the trail,” Serpa said. The travelers will work in pioneer fashion and eat and sleep in the wagons until they reach their destination, Independence, Ore.

What dangers will the wagon train encounter? Indians? Coyotes? No. Traffic.

The Oregon Trail is now mostly scenic highway where scores of automobiles will whizz by the wagons.

There is some prairie country and old country roads that the wagons will have to negotiate. One stretch, between Independence Rock, Wyo., and Border, Wyo., a trip of some 18 days at their 20-mile per day pace, may show the modern wagon crews some hardships more familiar to the first pioneers.

The area, in part, is a dry, dusty, rocky and barely populated stretch of no-man’s land.

Water will be carried in canteens with little possibility of a quick refill. At night, as the wagons form a protective circle, the riders will go to the one modern spot of the caravan: A 40-foot semitruck will follow with food. No chuck wagon. The victuals, however, will have to be prepared by the group.

To round out the repeat of western lore, a band of real Sioux Indians will “attack” the wagon train near Baynard, Neb. After the scuffle, a peace pipe ceremony and a buffalo barbecue is scheduled for both whites and Indians.

The wagons, made of sturdy oak, and in the same fashion as they were 100 years ago, were constructed by one of the Northwest’s few remaining wagoners, Roy Barbham, 60, Eugene, Ore. The Oregon Centennial Commission, which allocated $25,000 for the trip, paid $1,650 each for the six wagons.

The trail covers the northwest corner of Missouri, the northeast corner of Kansas, straight through Wyoming and Idaho to Boise, and into Oregon.

When the train reaches The Dalles, Ore., the wagons will forego the convenience of available modern highways and load onto barges for a trip on the Columbia River for as far as possible. This is the way early settlers did it, according to existing records.

The caravan is due at Independence Aug. 15.

Historic cavalcade wagon finally finds its place at new Heritage Museum site

(Published Jan. 26, 2022, in the Polk County (Oregon) Itemizer-Observer)

By Anne Scheck/Trammart News Service

INDEPENDENCE — This past fall, a celebrated symbol of city history, the “Cavalcade Wagon,” finally traveled from long-term storage to its new home at the Independence Heritage Museum. It carried with it memories of campfire sing-alongs, tick-picking “parties” and coffee brewed in a pot with a dead snake.

The prairie schooner look-alike represents a part of Independence’s past that was commemorated in 1959, when a group of intrepid Oregonians, and other enthusiasts, reprised the same journey along the Oregon trail that put some of the state’s early pioneers in Independence.

The re-enactment was known as the “On to Oregon Cavalcade.” The cavalcade wagon, with its rib-like hoops for the canvas cover, was one of seven like it on the trek – and the only one to stay in the destination city. It was wheeled out of a storage container, loaded onto a trailer, and then hauled to the museum’s new home, explained Amy Christensen, the museum’s curator.

Personnel from the city’s public works department pushed it into the building by way of the large garage entrance, she added. In fact, it probably wouldn’t ever have made the trip if not for the move of the museum to Second Street, across from the US Post Office.

The museum’s former site, at the historic 135-year-old Baptist Church on Third Street, simply couldn’t accommodate the large wooden vehicle. The one on display at the church actually was a reconstructed farm wagon.

So, this spring, when the Heritage Museum opens its doors after completing all the relocation and refurbishment, the public will get the opportunity to see the cavalcade wagon once again, after years in darkness. One of those who seems most pleased by the news is Richard Carter, the author of a book about the trip, “Trail Ruts.”

Carter, whose great grandmother died on the Oregon Trail in 1852, was one of about 70 members on the wagon train that retraced the original trip 63 years ago. It was undertaken to honor Oregon’s centennial.

Reached at his home in Washington, Carter said sometimes the experience seems like it took place an entire lifetime ago. At other times, it seems like only yesterday, he said.

From his perspective at the age of 92, he looks back on those days — being a young man traveling in a bumpy wagon across prairies and hills — as a period of life-changing lessons. However, at the time, he considered it mostly a great adventure.

The Conestoga-style wagons, which were built by putting new wood boxes atop running gear from those early trail rides, set out from the Missouri town of Independence, just as those early settlers did.

And, just like their predecessors, the cavalcade troupers faced hardship. Some challenges were similar — burning temperatures, fatigued or sick livestock, battles with biting insects — but some were the result of modern times, such as cars roaring down highways that startled the horses.

However, human nature in some proved to be a huge barrier, Carter recalled.

The leader of the group, a seasoned rancher named Tex, was a blunt speaking but highly competent individual. His unfiltered communication rubbed some people the wrong way, Carter recalled.

When some of the animals got distemper, Tex advised everyone to stop using a communal barrel for watering their hoof stock. When one man ignored that directive, and allowed an infected mule to drink, Tex toppled the barrel.

Carter, who was one of those who went to a nearby town to purchase scores of new buckets, recalled that Tex realized right away “that he should have handled this differently.” Nonetheless, it proved to be a turning point.

Soon there were a few “troublemakers” who spent time sniping about Tex’s leadership, he said.

“A big difference was that if the early pioneers clashed with their companions, they could separate themselves from the original group,” Carter said. “They did this by taking a different route, going on ahead, or falling behind,” he explained. There was no such option for the cavalcade.

“Because of traffic and supply conditions, our group had to stay together,” he said.

Carter was considered to have the most easy-going personality of nearly anyone on the trip, according to Jean Van Meter, who was one of the youngest adults in the group. In her early twenties at the time, she remembered starlit nights by a campfire, singing songs and cracking jokes about tick-picking parties – these good times usually originated with Carter, she recalled.

Carter, who played the guitar, often began strumming at the first crackle of the fire. As for those tick-picking parties, they were nothing to laugh about, Van Meter said. “Tick fever” sent one participant to the hospital. Everyone was on the lookout for the tiny bugs on fellow travelers, she said.

Carter recounted the time that “we went into a town, to a tavern, to have some fun, and eventually we all talked about it being time for a tick-picking party.”

“One guy took off his shirt, and sure enough, one was crawling on his chest,” Carter said.

Other unwelcome creature encounters weren’t amusing, either. After a pot of coffee was brewed and consumed during breakfast, a dead snake was found along with the used grounds when it came time to wash the container. This was seen as a willful act, not an accident in which the snake somehow crawled under the lid. “I can’t imagine the snake surmounting those difficulties to get inside the pot without human help,” Carter said.

Personality conflicts were quite visible, agreed Van Meter, who had carried the snake on a big spoon to show Carter the morning that the incident occurred.

However, her time with the wagon train was positive and life-altering, she stressed. She was a shy young woman who grew more confident and more extraverted during her months and miles on the trail, she said.

“This pushed me into meeting people, there were crowds all along the way,” said Van Meter, who still lives in Southern Oregon. The press coverage, at times, made worldwide headlines. At every stop, there seemed to be reporters, she said.

Does this notoriety make the cavalcade wagon a special feature of the museum? Not necessarily, according to Natascha Adams, manager of the Heritage Museum.

“It is on display along with many other artifacts that tell the story of Independence,” she stated, adding “we are trying to shift our focus at the museum to talking about all the other aspects of this area.”

“The pioneering story is important, but certainly not the only story,” she pointed out. “We want to make sure we honor people like the Kalapuya who were here for time immemorial, and the many other diverse groups that have resided in this location,” she said. “Our focus here is to begin to tell the stories that have gone untold.”

Three years ago, the Independence Library held a history-oriented scavenger hunt based on the facts surrounding the “On to Oregon Cavalcade.” Participants got clues to words for a crossword puzzle at certain storefront windows downtown. “I’m glad to see people are remembering this,” said Van Meter. “To me, of course, it was unforgettable.”