For about half a day, the pair of cactus wrens that visited our campsite constituted the wildlife highlight of our recent trip to Anza-Borrego Desert State Park.

They were perky and charismatic, with a call like a rusty door hinge, industriously hopping through our outdoor living area and plucking seeds and insects from the sand with curved beaks. As long as my partner Leslie and I remained motionless, the birds seemed unconcerned about our presence, and they patrolled our camp for several minutes, flitting to within a few feet of us at times. It was a charming and memorable way to start the day.

But that was before we encountered the enormous ground sloth mother with an infant on its back, a large raptor pinning a snake beneath its talons, and a dragon. Overshadowed by this menagerie, our memory of the wrens faded a bit.

We had traveled to San Diego County in mid-November primarily to keep a spa date for our adventure van at Agile Offroad in Santee. The company manufactures, sells and installs aftermarket gear, accessories and performance enhancements for camper rigs like ours, and Next Chapter was booked for some functional upgrades. The most notable of these were installation of a cell-service reception amplifier system and a heavy-duty cover for the rear differential to replace the flimsy stock version.

The cell booster would enhance our ability to use satellite mapping technology to find dispersed camp sites, which we typically employ once we’ve used paper maps and other navigational aids to pilot us to the general area we hope to explore. Boosters can’t produce a cell signal where there is none, but they can turn one bar of reception into two or three, and that’s generally the difference between having access to Google Maps or getting a “no network connection” message from your phone. The differential cover would replace one that is vulnerable to being ripped open by random rocks in off-highway travel, leading to catastrophic failure of a crucial component in the drive train.

This would not be our first visit to Agile in Next Chapter. In February 2021, just five months after we acquired the van, we brought it there to have a suspension upgrade installed, to cure the Sprinter’s natural propensity for excessive swaying and bouncing on irregular terrain. Afterward, we spent several days testing it out (successfully) in Anza-Borrego, on a camping and hiking trip that included a memorably close encounter with a herd of desert bighorn sheep in Borrego Palm Canyon.

Our itinerary this year had us driving to San Diego County on Sunday, dropping the van at Agile Offroad bright and early Monday morning, and heading to Anza-Borrego on Tuesday for two nights of open-desert camping before returning home on Thursday. It was a quick trip, hardly an eyeblink compared to our nearly monthlong adventures earlier this year along the Oregon and Santa Fe Trails, and into the Canadian Rockies. But it was a welcome reminder that new experiences and new discoveries await us even close to home and on ground we have covered before.

Gold in the mountains

The 200-mile drive from Ventura to Santee through the congested heart of metropolitan Southern California is a dismal slog, no matter what day or time you undertake it, and it was dark by the time we arrived at our Airbnb. The next morning we rose early and drove the short distance to the shop, dropped the van off shortly after 8 a.m., and walked 2 miles to a rental agency to pick up the car we’d reserved for the day.

And then we headed for the hills.

Our destination was the old gold-rush town of Julian, established in the 1870s at around 4,200 feet in the Cuyamaca Mountains. There’s not a lot to it — the charming heart of the town is a grid five blocks square, cupped in a fold between steep, wooded ridges — but it has historic buildings that house bakeries serving up Julian’s deservedly famous apple pies, some decent cafes, and at least one great brewery. Plus, quite a density of shops selling all sorts of themed merchandise, which during our mid-November visit trended heavily toward Christmas.

The drive to and from Julian was at least as scenic as the town itself. From Santee, we followed Interstate 8 east, and then took Highway 79 north into the mountains. The road is narrow and twisty, and as it reached the boundary of Cuyamaca Rancho State Park we found ourselves driving through a tunnel of autumn-tinged foliage, mostly California black oaks, a deciduous species whose leaves turn brilliant gold in fall. They lined the road and clung in patches to the mountain slopes above it like flaming islands amid a green sea of cedars and pines.

When we reached town, we strolled its sidewalks in crisp air under a robin’s-egg sky, wandering in and out of the shops. We had brews and barbecue for lunch at the Julian Beer Company, which also offered a line of hard ciders, apple production being (along with tourism) the local economic engine that replaced gold after the mines played out. We bought take-home slices of apple pie for a future camp breakfast, and we climbed the rocky hill at the north end of town to the Pioneer Cemetery on its summit, where we wandered among grave markers and blazing trees that framed views of Main Street.

Leaving town, we decided to make a loop of our day’s drive by following Highway 78 west and then Highway 67 south. Along the way, we stopped at the roadside Calico Cidery to explore the liquid expression of Julian’s apple heritage with a tasting flight of refreshingly tart ciders, enjoyed in a big barn with a view into the adjacent orchard. Then it was down from the mountains and back to Santee, where we retrieved our newly enhanced van as the sun set and returned the rental car.

The next morning, we headed for the desert.

Art among the rocks

The best route to the area in Anza-Borrego Desert State Park we planned to explore took us along the road to Julian that we had traveled the previous day. We didn’t have any deadlines this time, and we didn’t have far to drive, so we pulled off in Cuyamaca Rancho State Park at the Paso Picacho campground/trailhead and went for a hike to enjoy the golden woods up close.

It wasn’t really a hike so much as it was a saunter. (John Muir would have you always substitute the latter term for the former). And a fine saunter it was, 3 miles under another azure sky, through stands of glowing trees, with just enough nip in the air at 5,000 feet of elevation to require down sweaters. We slowly looped back to the van, ate our picnic lunch, and then proceeded on, losing altitude on the drive as we traded forested mountains for rocky bajadas and sandy washes dotted by creosote bush, yucca, barrel cactus and cholla.

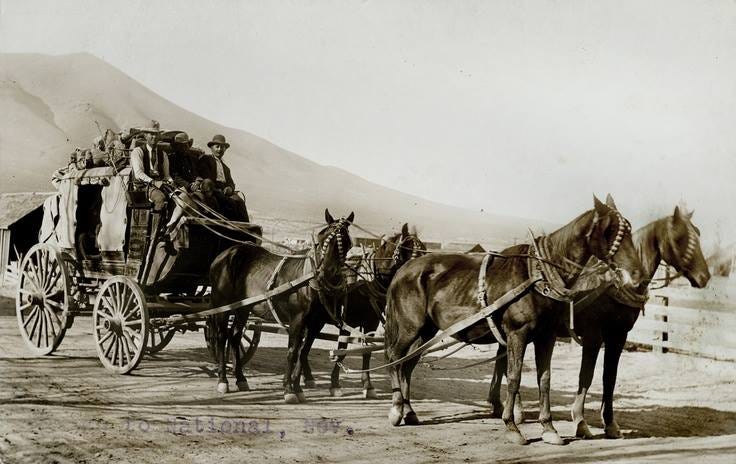

As we entered Anza-Borrego, we found ourselves traveling the route of the Butterfield Overland National Historic Trail, locally known as San Diego County Road S-2. Known at the time as the Butterfield Overland Mail Route, it was established in 1857 when John Butterfield won a $600,000 contract with Congress to deliver the U.S. mail from St. Louis, Mo., to San Francisco in 25 days or less. (The first delivery, in 1858, arrived in 23 days and 23.5 hours.) Butterfield was a former stagecoach driver from New York who founded his own livery company out west and later merged it with an express line founded by Henry Wells and William Fargo to form the American Express Company. The 1857 contract amount would be the equivalent of $21.8 million in today’s dollars.

The contract was suspended in 1861 when the Civil War broke out, not surprising considering that the 3,300-mile Butterfield route across the Southwest passed through the Confederate states of Arkansas and Texas. But the line’s twice-weekly mail coaches also were rendered somewhat superfluous by the completion of the first transcontinental telegraph network that year, and further by the completion of the first transcontinental railroad in 1869. Like the famed Pony Express, the Butterfield Overland Mail’s renown far outlasted its utility.

After a few miles on S-2 we left pavement and turned onto a dirt road leading into Blair Valley, a former lakebed bounded by ridges of granite, limestone, gneiss and schist — a geologic smorgasbord that tells a tale of quiet sedimentary deposition followed by violent, transmogrifying magmatic intrusion. There’s a semi-developed primitive campground just off the highway there but we continued past it along the deeply sandy track, on our way to a boondocking site Leslie had scoped out using Google’s satellite imagery and our newly enhanced cell capability.

We didn’t make it. After several miles in four-wheel drive along the sketchy track, we came upon a stalled two-wheel-drive sedan, its front wheels buried in the sand. We could not drive around it, and when a friend of the driver arrived to dig the vehicle out using a tiny hand trowel, we realized we would be sitting there for hours unless we backtracked to an alternative route and circumvented the blockage. It was impossible to turn around without crushing native vegetation, so Leslie heroically backed us up about a quarter mile along the curvy, sandy track, using the rear-view camera, to reach the secondary road. We followed it to a good campsite in a cove nestled against the rocky ridge, and settled in for the night.

The next day we hiked. Er, sauntered. (In so doing, we were also paying a silent homage to the memory of a dear friend to both of us, Richard Pidduck, a leader in the local agricultural community who died suddenly and unexpectedly earlier this year. At a memorial this summer, his son Will recounted Richard’s wholehearted endorsement of Muir’s insistence on the superiority of “saunter” over “hike” as the proper term for exploring the outdoors on foot — something Richard loved to do at least as much as Leslie and I — and urged those in attendance to seek out a saunter in Richard’s memory. We are always happy to comply.)

There’s a 6,000-year history of human habitation in this part of the Sonoran Desert, a subregion also known as the Colorado Desert. At the time of European contact, the indigenous Cahuilla occupied the mountainous north and the Kumeyaay the south, their territories overlapping in the central area, and Blair Valley contains evidence of modern indigenous occupation dating back several hundred years. Two developed trails lead into canyons with boulders and bedrock outcrops bearing pictographs, mortars and metates used to grind seeds and nuts, and cupules, small depressions pecked into the rock that are too shallow to be utilitarian and are assumed to have served a spiritual or symbolic purpose. Together these sites are identified as the Little Blair Valley Cultural Area, and likely represent early Kumeyaay habitation.

We spent several hours exploring the canyons and their mysteries, and then sought a new place to spend the night. We settled on the boondocking site we had originally been seeking the day before, when we were blocked by the foundered motorist, and we were glad we moved. The second site was more secluded than the first, its vegetation more botanically diverse, and it was located on a bench higher on the slope, so it had a better view across the valley. It also delivered the enchanting cactus wren visit we enjoyed on our final morning in camp.

From Blair Valley we headed toward the town of Borrego Springs, which sprawls across the sandy floor of the Borrego Valley at the foot of the San Ysidro Mountains. As we approached, we had our first encounter with the surreal wildlife that also calls the valley home: A rust-red metallic sculpture of a giant raptor, modeled after a very real bird once found in the Southwest called Aiolornis incredibilis, a member of an extinct family of birds called teratorns. Incredibilis is believed to have been the largest flying bird ever to live, weighing 50 pounds, with a body length of 5 feet and a wingspan of up to 18 feet. It and its fellow teratorn species last adorned the skies over the Americas 10,000 years ago.

The teratorn is one of 130 works that constitute one of the most remarkable outdoor sculpture gardens on the planet. Scattered across 1,500 acres of desert sand and scrub known as Galleta Meadows Estates, the artworks were commissioned by the property owner, Dennis Avery (heir to the Avery label-making fortune), and created by Ricardo Breceda, a self-taught welder and artist. The Borrego Valley land and its monumental decorations are now held by the nonprofit Under the Sun Foundation, which refers to them as the “Sky Art” collection.

The works are divided into three general categories: prehistoric creatures inspired by the lavishly illustrated book Fossil Treasures of the Anza-Borrego Desert, art work inspired by the region’s human and natural history, and pieces “inspired by whim and fantasy,” which includes dinosaurs that never lived in California as well as the dragon we encountered. (The Sky Art materials actually refer to that as the Serpent, but while that name may describe its wingless body it certainly does not adequately capture the fierce majesty of its head.)

And they are astonishing — monumental, intricately detailed, imaginative and expertly crafted, their oxidized surfaces perfectly suited to the palette of the arid landscape within which they reside. We visited several on the edge of town; scores more are distributed farther afield. All are accessible by formal and informal dirt roads, and you could spend days tracking them all down. Perhaps someday we will.

Before beginning the long slog north across Metro SoCal toward home, we paused amid the sculpture garden to enjoy our picnic lunch in the van. With a view of a dragon.

I enjoyed this log very much. It brought back fond memories of when we used to go to our Cuyamaca mountain cabin. We'd stop in Julian and get an ice cream float, groceries and a block of ice to put in the icebox at the cabin. We'd pass through Isabell and head up into Julian. Such fun times. The cabin was out past Cuyamaca Lake up in the National Forest. It was burned down in the big San Diego fire, but my cousin has built back a very different cabin and he lives there. Such a beautiful place before the fire. Lots of trees have grown back. My dad and I took down seeding pine trees and we planted them all around our cabin. A lot of them made it and they are pretty big now. Obviously we didn't set out any kind of watering method for them. Thanks John, I always enjoy reading your posts, its almost like we the readers are there with you and Leslie.

Always enjoy being able to tag along on your travels

Thanks John