The Huerfano Heritage Center occupies a nondescript storefront on West Sixth Street in Walsenburg, Colo., sandwiched between a pair of aging hotels. Operated by the Huerfano County Historical Society, it’s open to the public for only a few hours a week, and Leslie and I had timed our arrival carefully. But when we tried the front door during a visit in August, it was locked.

As we peered through the dusty windows, we spotted the docent, John VanKeuren, hurrying toward us from a back room. He unlocked the door and welcomed us in, apologizing for his tardiness in opening the center; he had been tending to the plants and forgot to unlock the door. He doubles as the docent at the Walsenburg Mining Museum, also operated by the Huerfano County Historical Society, where we had met him that morning, and apparently is almost singlehandedly keeping Walsenburg’s memories intact. They reside in archival boxes and the bound pages of old newspapers, all gathered and indexed and arranged neatly on shelves and in drawers in the old storefront

“So,” he said, “what do you want to know?”

What, indeed.

In the history of any family, there are countless forks in the road, each junction representing an individual choice — or perhaps just a pivotal event that had nothing to do with judgment or volition but reflected merely the blind workings of chance — that foreclosed some possible futures for that family and unveiled others. Some of these deflection points are so subtle as to be imperceptible at the time, while others arrive as forcefully as a tornado.

In the landscape of my family history, a tornado touched down on March 15, 1946. That’s the day my paternal grandfather died in the Pictou coal mine just outside of Walsenburg. According to the Colorado Mine Accident Index, my grandfather was the victim of “roof fall,” bland words that elide the horror of being crushed by collapsing rock in the darkness of a cramped underground tunnel.

That event blew my father’s teenage world apart, sending him, his younger brother and their abruptly widowed mother onto new life trajectories. Beyond that existential fork in the road, one of those trajectories would lead 12 years later to me, and to everything my life has been.

Both my parents died in December 2022, forever silencing the untold stories they might have shared about their past. They told us many while they were alive, of course, and because my Mom never strayed very far from the Northern California towns where she was born and grew up, I’m intimately familiar with the landscape of her life — it is largely the landscape of my own childhood as well.

Dad’s early years, however, played out on a landscape I had never seen and one that he described to us only in sketchy outline. We humans are a place-based species, our interior lives shaped to large degree by our exterior surroundings, and my lack of first-hand knowledge about Dad’s native ground has long felt like a gap in need of bridging. I also wanted to satisfy my general curiosity about the place where such a pivotal event in our family story occurred.

So in August, Leslie and I embarked on a road trip into the past, to explore the landscape of family tragedy in the hope of better understanding my father and the many-branched road that brought our family to now.

What did I want to know? To be honest, I was not sure. I have many questions about Dad’s past, but most can’t be answered at a place like the Heritage Center.

“Why don’t we start by looking up my grandfather’s obituary,” I suggested.

Not all that glitters

Colorado is littered with old mining towns that have become tourist attractions, leveraging their boom-and-bust past to build a more durable economic foundation based on hospitality and recreation — more-renewable resources than the quickly exhausted veins of gold, silver, lead and zinc that powered their founding.

Walsenburg is not one of them.

It’s a mining town, or was. But unlike its more famous Colorado counterparts — Telluride, Silverton, Breckenridge — it lacks a showy alpine setting, and its principal ore lacks the romantic allure of precious metals. Walsenburg is a time-worn former coal town at the scrubby edge of the Great Plains. The years have not treated it well, and it has been declining since the local coal industry shut down in the 1950s. The population peaked at nearly 6,000 in 1940; today it stands at half that. The wreckage of the Walsen mine power plant on the outskirts of town is one of the few physical reminders of Walsenburg’s glory years.

Colorado’s coal history — and so a branch of my own family history, in a very roundabout way — begins about 65 million years ago. The part of the planet that now constitutes southeastern Colorado was mostly under a tropical sea then, but the infant Rocky Mountains were slowly nudging the shoreline to the east as they poked skyward. Along the sea’s shoreline, vast swampy lowlands emerged at the margins of the rising mountain range, similar in biological construct to today’s Everglades only with more gigantic vegetation.

As the mountains rose, sediment eroding from their flanks sluiced downward and buried successive bands of swampy forests, condemning them to anaerobic and therefore only partial decomposition. The peaty result, subjected over millions of years to subterranean heat and pressure, lithified into various grades of coal. Continued uplift and subsequent erosion eventually uncovered those coal seams, or removed enough overburden that they could be accessed through relatively shallow tunnels dug from the surface. In the late 1800s and early 1900s, these mines drew thousands of immigrants from Europe searching for political stability and economic opportunity in America.

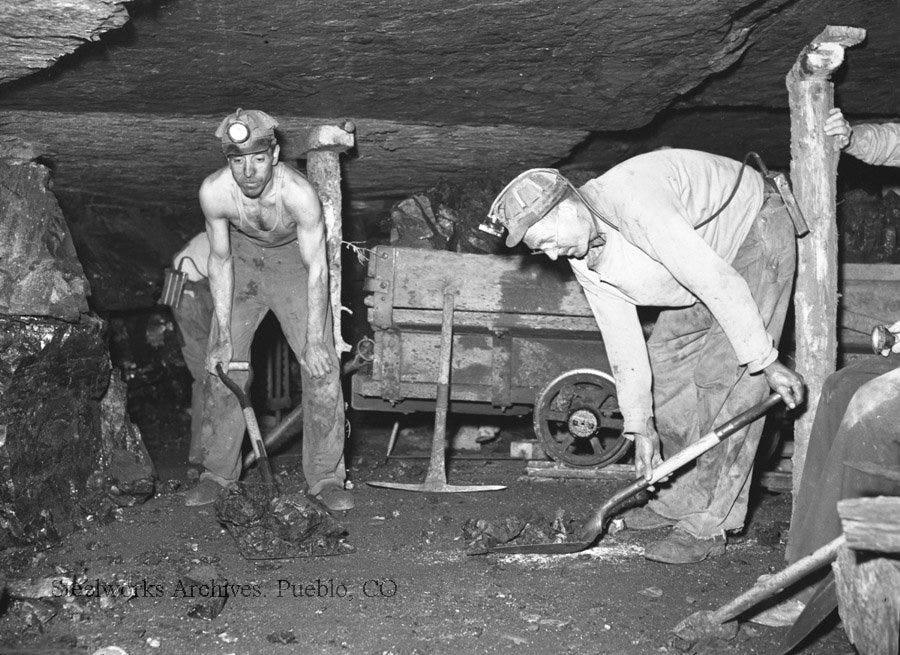

Archival photos from Colorado mines in the early 20th century portray the work as a claustrophobe’s nightmare: Stygian darkness illuminated only by headlamps or the photographer’s flash, narrow tunnels, wooden props fashioned out of peeled logs supporting a soot-black roof often too low for a grown man to stand upright.

When his father was killed, my dad was 16. He was born in Walsenberg in 1929 to John Albert Krist and Margaret Cernusco Krist, who welcomed their firstborn just in time for the Great Depression. Both his parents were the children of immigrants — on his father’s side from Slovenia, on his mother’s from Italy — and my Dad’s early years were spent in a polyglot community of eastern and southern Europeans.

My dad turned out to be a musically gifted, playing professionally from a very young age, and had hopes of going to college after high school to study music. His dad’s death slammed that door shut, and instead he joined the Navy when he was 17, graduated from the Naval School of Music in Virginia, and for seven years played in Navy bands while traveling the world aboard the aircraft carrier USS Coral Sea and the battleship USS Iowa. He was stationed for a while in San Diego and at Pearl Harbor on the island of Oahu, landscapes that must have seemed like an exotic fantasy to a coal-town kid from the semi-arid plains at the foot of the Rockies.

After he left the Navy, Dad returned to California, settling in Petaluma near his mom and younger brother, who had moved West while he was away. I remember him talking about this only once, in the last year of his life, but it must have been an enduring emotional blow to have left home so young, and to have spent seven years dreaming about someday returning, only to find that the “home” he dreamt of no longer existed by the time his enlistment ended.

In our conversation, he referred to this as the time he “lost everything,” which strictly speaking was not true, but surely reflects the sense of dislocation he felt as a young man trying to establish roots in an unfamiliar place, the focal point of his childhood metaphorically erased during his absence. I suspect it also reflected the rippling repercussions of that March day in 1946 when an accident in a coal mine ended the life he and his family had known and all the plans they had for the future.

While living in Petaluma, he enrolled at Santa Rosa Junior College, and it was there that he met my Mom, when both were playing in the SRJC band. They married in 1957, moved to San Francisco, and I was born a year later.

Were it not for that fatal accident in the Pictou, none of those things would have happened.

In the company of ghosts

Our route to Walsenburg this summer took Leslie and me and our Next Chapter van along Interstate 40 through the desert in a heat wave (118 degrees in Needles the day we crossed the Colorado River into Arizona). Further along, we headed up into the welcome coolness of the pine-studded mountains around Santa Fe and Taos, New Mexico, where we fended off cloudbursts during van-rattling thunderstorms. From Taos, we cut east to I-25, which runs north-south along the foot of the Rocky Mountain front range all the way from New Mexico to Wyoming.

At Trinidad, another Colorado coal-belt town, we left the freeway for Highway 12, a rural route that curls around the landmark Spanish Peaks. Visible from just about everywhere in the region, the peaks are a pair of huge volcanic intrusions that were uplifted along with the nearby Sangre de Cristo range during the Laramide orogeny that raised the Rockies. In the indigenous Comanche language, the Spanish Peaks are known as Wahatoya, “the breasts of the Earth,” an altogether more colorful name.

The highway climbs over Cuchara Pass at 9,941 feet before dropping into the valley of the Cucharas River and following it through the small community of La Veta toward Walsenburg. Just west of town, we followed a network of dirt roads off the highway to a private site we’d rented, and set up our base camp in rolling hills clothed with sagebrush, pinyons and junipers.

The detour over Cuchara Pass was strategic: Among the few stories Dad told about his childhood, the cool mountain meadows along the Cucharas River figured prominently as the setting for traditional 4th of July picnic gatherings of Walsenburg miners and their families. Another favorite story featured family mushroom-foraging expeditions into the forested flanks of the mountains, which involved great batches of polenta and other traditional Italian foods cooked outdoors over a fire.

We learned in August that the forest is still lush, and that the mountains still provide cool refuge from the sun-baked plains around Walsenburg. We picnicked there ourselves that day, enjoying our lunch under aspens along a small creek. Vacation-home developments, however, have swallowed the expansive meadows that once hosted miners’ picnics, their grassy remnants chopped up by subdivision streets.

My own memories of Dad’s Walsenburg stories and the places they were set are thin and tenuous, but we had an expert tour guide during our days there. In August 1997, my parents traveled to Walsenburg for the 50-year reunion of Dad’s high school graduating class. Mom kept a journal of their travels in those days and I used her account of their two-week trip 26 years ago to help me identify destinations for our itinerary this summer.

It was not as good as being able to actually visit Colorado with my folks, but it was close. As we drove around and explored, I had Dad’s reminiscences — as recorded and interpreted by my Mom — to guide us. It was like being led by helpful ghosts.

Among the places we explored was St. Mary’s Cemetery on the edge of town, where I located the Krist family plot and the graves of some of my relatives. We also visited the sites of abandoned Colorado Fuel and Iron (CF&I) company towns at the Pictou and Cameron mines, where my grandfather worked.

Walsenburg is surrounded by hundreds of square miles of largely empty land that’s off limits to meaningful development because a vast subterranean honeycomb of mining tunnels makes the ground prone to abrupt collapse. At Pictou, there was not much to see but heaps of old mine tailings fenced off on private lots. At Cameron, however, the rolling topography is accessible by an unpaved county road that winds among the concrete foundations of hundreds of structures once comprising the mining camp known as Farr: a self-contained community of homes, recreational facilities, stores, a school, and all the vast infrastructure associated with extracting, processing and shipping coal.

It was a silent and empty imprint of industry, barely hinting at the bustle of life, death and commerce that once animated it. More ghosts.

All that we leave behind

Back at the Huerfano Heritage Center, John VanKeuren pulled a binder from a shelf. It contained a meticulous index to every obituary ever published in the county’s newspapers, principally the Huerfano World and the World-Independent. The entries are organized alphabetically by last name, and include the date of publication, the name of the newspaper, and the page on which the obit appeared.

I leafed through it and quickly found a listing of deceased Krists, a rather unsettling experience. I located my grandfather’s entry, and John pulled out a bound volume of World-Independent issues that included those for March 1946.

It wasn’t really an obit; it was a news story, on the front page above the fold. The headline reads “John Krist, Jr. Killed in Pictou Mishap.” The subhead adds details: “Veteran Miner Dies Instantly of Broken Neck.”

“John Krist Jr., 41, a miner at the Pictou mine of the Colorado Fuel and Iron corporation, was killed instantly at 1 o’clock this afternoon when he was struck by a fall of rock,” the story reads. “Others working near him said a ‘pot’ of rock fell without warning, striking him on the head. This is the first fatality recorded in the new mine, which was opened early this year. Krist was at work loading coal with his brother, Rudy, when the accident occurred. Rudy was uninjured, however. Both the brothers recently were transferred from Robinson No. 4 mine at Farr, to work in the new property. The deceased is a miner of 15 years’ experience with the CF&I corporation, and was listed as an expert miner.”

The details were new to me, and revealed layers to the tragedy. The accident widowed my grandmother and set my Dad and his brother adrift in boyhood without a father, but I can only imagine the lasting trauma Rudy experienced seeing his brother cut down next to him. Nevertheless, he remained in Walsenburg and died there in 2001 at the age of 91, according to his obit in the Huerfano World.

Leslie and I spent a couple hours with John, getting to know these lost members of my family by looking up obituaries and related stories. We found a front-page photo of my great-grandparents, who emigrated to coal country at the turn of the century from a tiny village in Europe, celebrating their 50th wedding anniversary with a big party at their home on West Seventh Street. We learned also that great-grandmother Mary died four days after the celebration. Her obit was also on the front page, and described her as “a pioneer of Huerfano County.”

Her husband moved a couple years later to Long Beach in California, where one of their daughters lived, and died there in 1952 at the age of 76. His obit, which referred to him still as a “Walsenburg Man” in the headline, noted — approvingly, I think — that his body would be returned home for burial; he and Mary are in the family cemetery plot.

John also sat us down in front of a large computer monitor and pulled up digitized historical photos from the Heritage Center archives, all of them representing a docent’s careful sorting and organizing of family photo albums and boxes of memorabilia donated to the Historical Society. We scrolled through scores of images of mines and miners, but also of schoolchildren and baseball teams, swimming pools and locomotives, coal cars and picnics and dances and strife – notably the legendary “coalfield war” of the early 1900s, in which Walsenburg played a prominent role.

With the hindsight of 77 years, I can say that my Dad’s life journey after Walsenburg turned out well. But after our time in the Colorado coalfields and archives, I have a new appreciation of how utterly lost and alone he must have felt as that train pulled out of town with him on board, bound for the East Coast. One lesson to draw from those photos of activity in the coal camps and nearby mining towns is the importance of community and family in making bearable a way of life predicated on a dangerous, exploitive and brutalizing occupation. Leaving for the Navy at 17 saved Dad from a life in the mines, the destiny of so many sons of coal miners, but it also carried him away from the embrace of family and friends to a distant and unfamiliar place where he knew no one.

He adjusted, of course. Humans are resilient creatures. And if I shift my gaze westward from Colorado, I can fast-forward through all the years that came after Dad left Walsenburg, as he set down roots in the new soil of Northern California, built a life, raised a family and lived out his days in the supporting embrace of his wife, his children, his grandchildren and a network of friends. He may never really have gotten over the sense of loss that rippled across the decades from that terrible March day in 1946, but he moved on and did his best to chart a new course. There’s a lesson in that, too.

John: Every time I read a post I say to myself, "You don't have to comment on every post, Tim." But each time I am drawn to the comments. Damn you. LOL. There is so much richness in these posts, John. In this post, so much pathos. So much KRIST. Your perspectives and empathy for your dad are generous and honest. Thanks for this one. (And might I shout out for Leslie - your steadfast ally on these trips. She's a prize.

Hi John - I came across this post in my own search for connections to my family story. I think we might be distantly related. I am a descendent of Krists who lived in Walsenburg. My grandparents spent much of their childhood in Tioga, CO which incorporated the Pictou mine. The land is now owned by my family, and my grandpa can point out what each foundation was at the time when the mine was still open and before it became a ghost town. I shared your story with my grandmother and she believes your grandfather may have been her uncle, though her memory is starting to fail. I'm not sure if I would be able to fill in any gaps for you, but would be happy to connect.