There’s a triptych of framed sepia-toned photographs on the wall just outside my home office that has traveled with me each time I have moved over the past four decades.

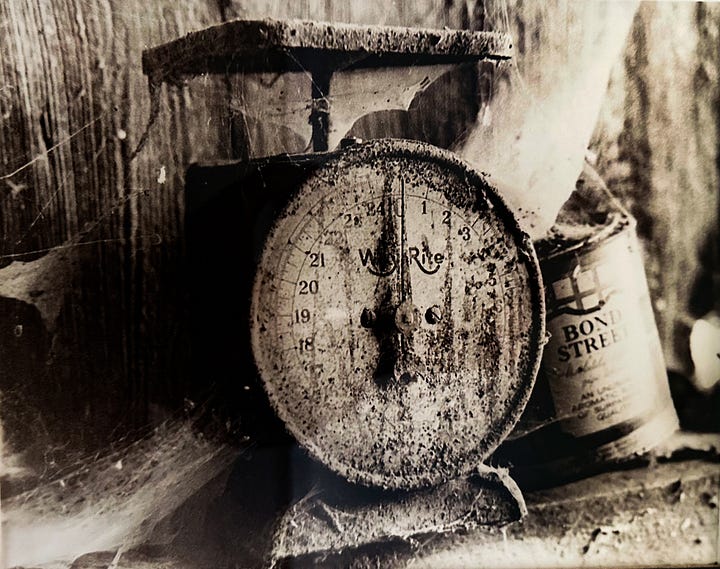

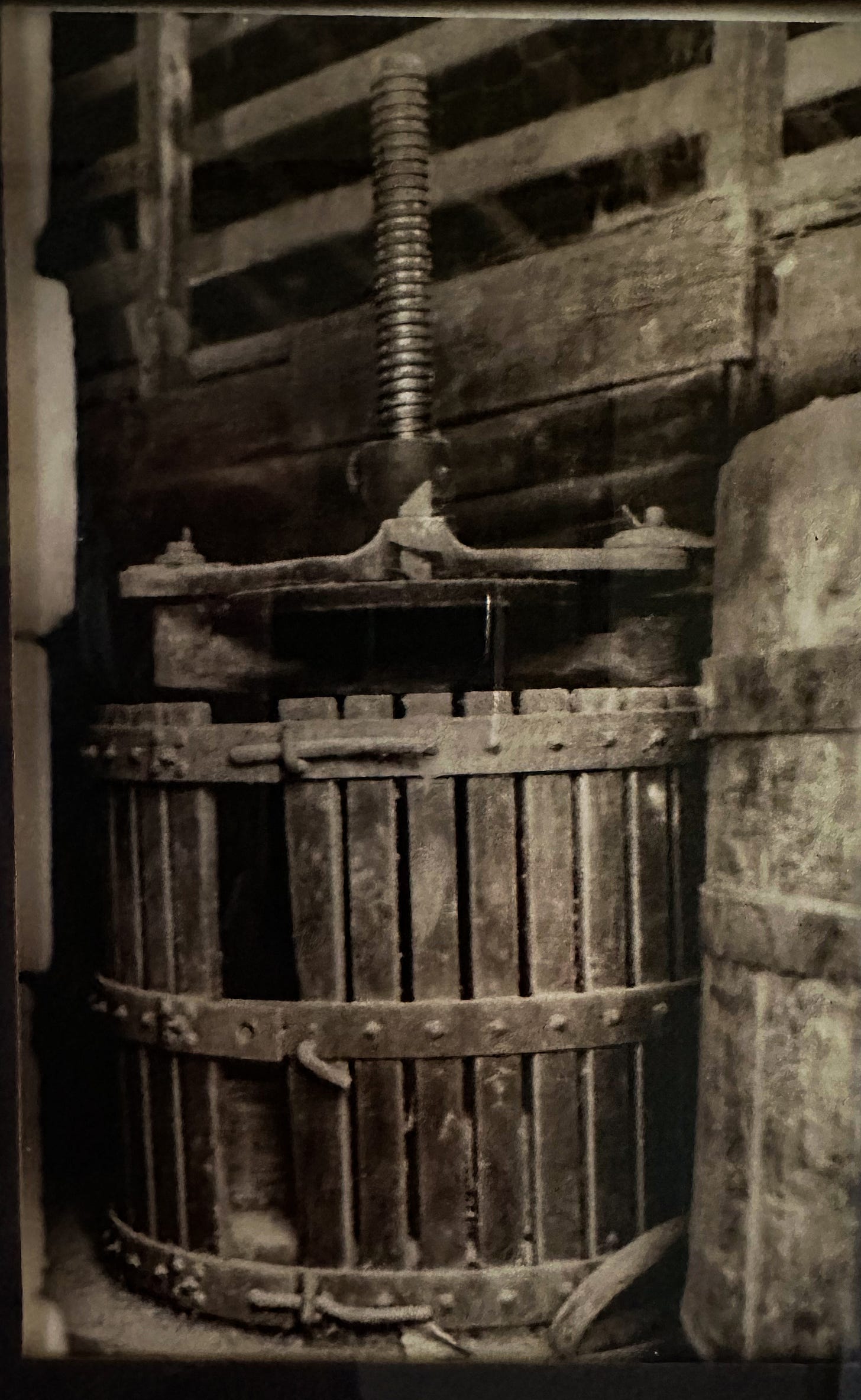

One portrays vintage winemaking equipment — a grape press and a redwood fermentation tank — in the shadowy corner of an old barn. Another captures the weathered siding of a farm outbuilding being engulfed by wild blackberry vines. The third is of a cobwebbed kitchen scale on a rough wooden shelf thick with dust. Together they suggest a provenance of some antiquity, as if they capture scenes from a 19th century ghost town.

In a way they do. But they’re not really that old. I shot them in the mid-1980s, and developed the negatives and the prints in my bathroom darkroom. They’re no more antique than I am (please hold the quips), but they do capture images of a way of life that has passed: that of my childhood and the rural landscape where it took place.

They were taken on the ranch my family bought in the early 1960s in Northern California’s Sonoma County, midway between the towns of Santa Rosa and Sebastopol. We moved there when I was 5, and I lived there until I left for college in Santa Barbara 15 years later. My siblings and I, having inherited our parents’ 50% stake in the property when they died in December 2022, have been working for nearly two years with our cousins (whose father, our dad’s brother, owns the other 50%) to prepare it for sale. This has involved a lot of brush clearance, debris removal, and reminiscence about our time on that land. (I wrote about camping there in my December 2023 Next Chapter Notes essay “Ghost Town.”)

We’re hopeful that after many months of work, the long-neglected ranch will find a new owner this year, one who will restore it to at least some version of its historical productivity. And that prospect — that after more than 60 years, this Northern California orchard and vineyard land will cease to be an ongoing element of our family story, becoming only memories and old photos — has me thinking about all the roles that piece of ground has played as a home to humans over the centuries.

It’s similar to the way Leslie and I approach most of the places we visit during our Next Chapter adventures on the road. Although we choose destinations for many reasons, including their wildness and physical beauty, we are alert to the stories of human continuity on those landscapes over decades, centuries, even millennia, that also contribute to the richness of the experience of being there. Stories about places are often stories about the people who have cherished them, fought over them, despoiled them, protected them, or simply called them home.

I do not really know all the stories that have played out on my home ground over the centuries. But as those photos on my wall suggest, I have collected some clues over the years. And while I am waiting for our next journey on the open road, I thought I would apply the kind of research to the history of my former home that I usually apply to other spaces we visit in the West and beyond.

The blade

The oldest clue in my collection is a small flaked-obsidian tool, perhaps a cutting blade or hide scraper. I found it one day while walking along the creek that bisected our 23-acre ranch, which when we bought it was planted with wine grapes and prune trees.

I have no idea what other artifacts might have been associated with that site; land that has been repeatedly tilled, plowed and planted for commercial agriculture over more than a century has little undisturbed evidence to offer the pre-teen archaeologist. But the place where I picked up and pocketed that carefully knapped blade of volcanic glass as a boy was near a seep that kept water year-round in the adjacent stretch of creek, much of which otherwise dried up in the summer.

In the absence of active management over the past 30-plus years, native species have recolonized much of the ranch, allowing me to picture what the scene might have looked like before Euro-American settlement: a perennial spring, a lazy creek supporting willows and other basketry materials, the surrounding slopes covered by acorn-rich oak woodland inhabited by rabbits, quail, deer and other game. For Indigenous hunter-gatherers, it would have been an attractive place to live or at least to camp seasonally.

According to the searchable interactive map of the Americas maintained by Native Land Digital, an Indigenous-led nonprofit based in Canada, our family’s ranch was (and still is) within the homeland of the Southern Pomo People. Besides Sebastopol and Santa Rosa, their territory included what is today Trione-Annadel State Park, a hilly landscape where volcanic deposits include obsidian outcrops. The Southern Pomo quarried and traded material from that source widely, and they used it to make a variety of tools.

Which means Annadel is the most likely source of the glass used to fashion the blade I found in the vineyard one long-ago summer day. It sits on a shelf in my home office now, a reminder that for thousands of years before my family called that piece of ground home, it was treasured by others, and that unlike us, they did not leave it of their own volition.

The plow

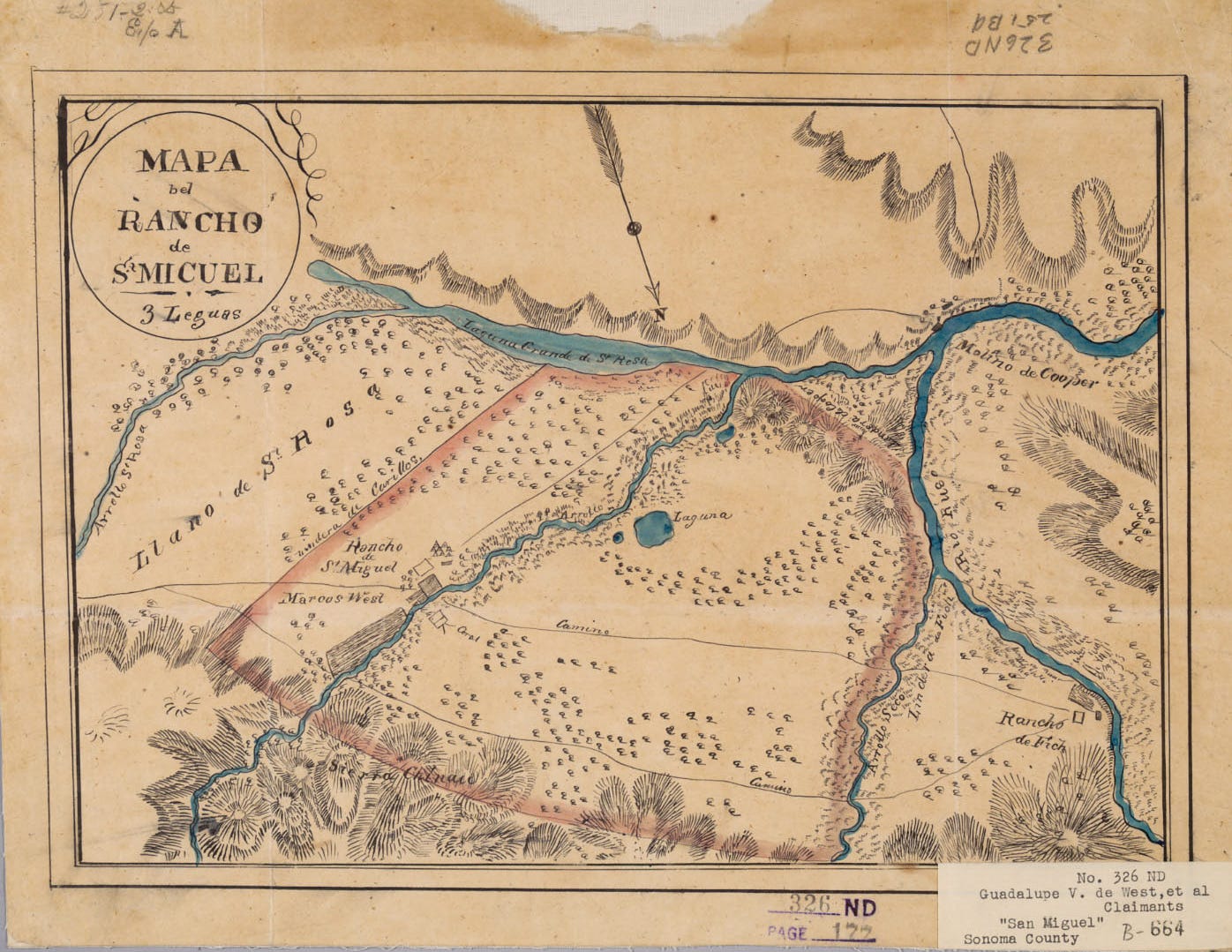

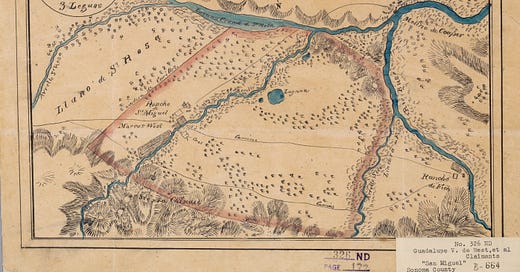

The end of Southern Pomo tenure on that land probably came in 1840, or at least that is when newcomers laid claim to it. That’s the year Juan Alvarado, the Mexican governor of Alta California, granted a petition for 6,663 acres of land filed by Scottish immigrant William Marcus West, who was married to the niece of the governor’s cousin, Mariano Vallejo. Known as Rancho San Miguel, the land grant included what would eventually become our ranch.

West died in 1849, a year after Alta California was turned over to the United States through the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo at the conclusion of the Mexican-American War, leaving the property to his wife and seven children. The transition from Mexican to American rule was problematic for landowners whose title was based upon Spanish or Mexican land grants, for they were almost never documented and surveyed in the manner U.S. law recognized. Typically, the only documentation consisted of a notation in the governor’s land-grant record book and a diseño (Spanish for “design”): a hand-drawn map depicting natural landscape features that roughly described the setting and boundaries of the property, typically filed with the petition for a land grant.

When West’s heirs filed for title to their land under the Americans, legal disputes arose over the dimensions of the grant that were not resolved until the matter reached the U.S. Supreme Court, which in 1859 ruled in favor of West’s wife, Guadalupe. She finally acquired title under U.S. law in 1865.

Apparently the land did not stay in the West family’s hands for very long after that. According to Sonoma County title records, the section of Rancho San Miguel that includes my childhood home was acquired at some point by Nicholas Carriger, a prominent area landowner who arrived in Sonoma in 1846, made his fortune on the American River during the California gold rush, and with it bought a thousand acres of farmland in the Sonoma Valley. The stately home he built there in 1860 is a historic landmark.

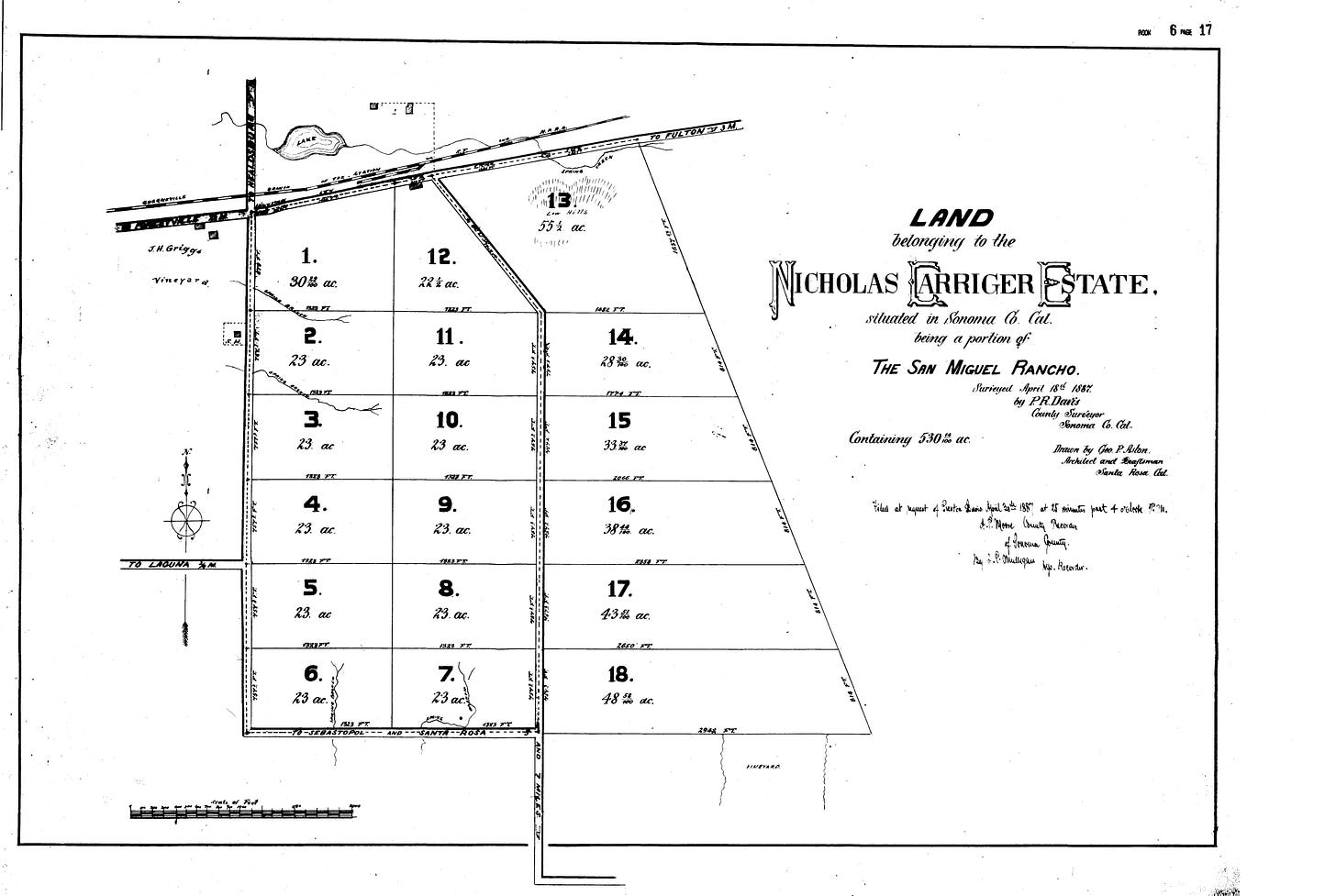

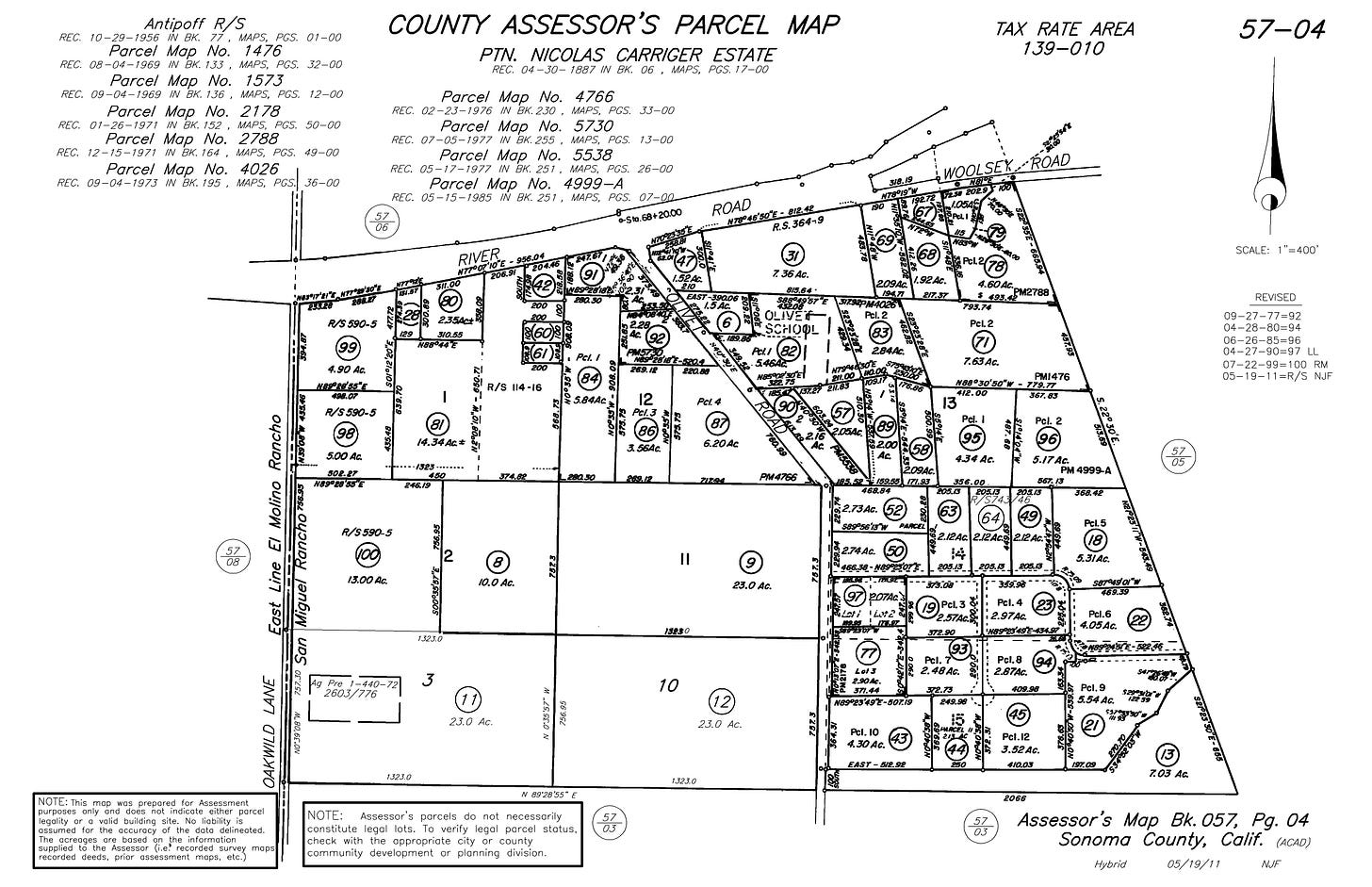

Carriger died in 1885. Two years later the land in the Russian River Valley that includes my family’s ranch — then owned by the Nicholas Carriger Estate — was surveyed and its 530 acres subdivided into 18 parcels. According to the subdivision map filed in 1887 with the county, most of them were 23-acre rectangles, like our ranch, although they ranged in size from 22 to 48 acres. That small-farm vision for the entire estate did not last; many of the parcels were subdivided again and again over the decades into smaller rural residential lots.

It’s unclear who purchased the parcel that became our ranch from the Carriger Estate. But the development of that property as something more than raw ground may have commenced around the turn of the century. According to an appraisal by the county assessor in the 1960s, the house I grew up in was constructed in 1906. That was followed by construction of a “cabin” in 1936, and a second house in 1947.

We bought the property from the Del Rosso family, who may have been part of a wave of Italian immigrants who settled in the Santa Rosa area in the 1880s and 1890s. Many of the newcomers found work in the area’s basalt quarries, saving their wages until they could afford to buy property of their own, and many ended up in the grape-growing and winery businesses. Whether the Del Rosso family bought the ranch directly from the Carriger Estate or a succeeding owner is unknown to me. But when I was growing up there, the outbuildings contained other clues about its history.

In our day, the big redwood barn was used mainly to store the field boxes and buckets we used during grape and prune harvests, along with a tall stack of redwood trays that in an earlier time had been used to dry fruit in the sun. But it also had an extension on one end with a livestock stall in it, above which an old leather horse collar and harness gear hung on the wall. In the rafters of the nearby tractor shed was a steel-bladed plow with a long-handled wooden frame, designed to be pulled by an animal not a tractor.

The implication of these seems fairly clear: Before there were machinery, a vineyard and an orchard on the land, someone walked behind a plow harnessed to a horse or mule preparing its soil for other crops. The presence of an old horse-drawn hay rake near the barn suggests one possibility for those crops, and implies that raising cattle may have been part of the pre-vineyard/orchard operation.

The press

When we moved onto the ranch in 1963, besides the 12 acres of vines and 8 acres of orchard there were four large redwood chicken coops distributed among 3 acres of houses and outbuildings. For a time, we raised chickens ourselves in half of one of the coops, a small flock that kept us supplied with eggs (and terrified those of us kids tasked with gathering them from antagonistic hens determined to incubate them). We repurposed the other henhouses for storage, a workshop and a garage. But the collective scale of those structures suggests that at one time in its history, there was commercial-scale egg production on the ranch, as the volume produced in four henhouses with an aggregate area of several thousand square feet (the largest was 110 feet long and 24 feet wide) would have outpaced the demand of even several households.

That would not be surprising. There’s a long history of commercial egg production in Sonoma and Marin counties; when I was growing up, one of my best friends lived on a ranch where his parents operated an egg facility with tens of thousands of laying hens.

But the somewhat ambiguous clue to our ranch’s past I find most intriguing is captured in one of those photos that hang in the hall outside my home office.

The vineyard on the ranch, old even we moved there, probably was planted between 1900 and 1920. My hunch in that regard is based on several observations. First, phylloxera — an insect pest that feeds on grapevine roots, damaging them and initiating secondary fungal and bacterial infections — wiped out most of the vineyards in California in the 1880s and 1890s. The plague was not stopped until vineyard owners replaced vines on vulnerable European rootstocks with vines grafted onto phylloxera-resistant rootstocks native to North America.

Second, the onset of Prohibition in 1920 pretty much put a halt to new vineyard development. Some wine production was still allowed for medicinal or religious uses, but without a legal mass market, hundreds of the state’s wineries closed. Vineyards throughout wine country were abandoned as grape demand plummeted.

And third, our vineyard was unlikely to have been planted after Prohibition ended in 1933 because of its unusual mix of varietals — zinfandel, petit sirah and carignane — that were intended to be harvested, pressed and fermented together, producing what was known as a “field-blend zinfandel.” Such vineyards were seldom planted after the early 1940s, when federal law changed and outlawed the sale of wine labeled as a specific varietal such as “zinfandel” unless at least 75% of the grapes used to make it were that single variety. (We hauled our grapes to the Italian Swiss Colony winery in Asti, where they were incorporated into a generic red.)

So, back to the photo of a grape press and fermentation barrel in our old barn. Their size seems out of scale for producing wine for household consumption, unless your household drinks 500 gallons of wine a year (not impossible, but unlikely). Yet a 12-acre vineyard by itself is too small to support a true commercial operation, and we had no evidence of a winery on the property that might have pressed grapes from other ranches. So what is the presence of that equipment in that barn telling me about the history of the ranch where my siblings and I grew up?

I do not know. It probably will always remain a mystery. But I like to imagine a scenario in which previous stewards of that land survived the national lunacy of Prohibition and the hard times of the Great Depression — and saved their farm — by bootlegging wine for all their friends, family members and neighbors. As a longtime fan of old-vine Sonoma County zinfandel, I would happily claim that heritage. Salud!

What a grand history and as others have said, your writing skills are so appreciated in these times. I love the reference to being terrified by the chickens during egg retrieval. I tell people that my girls turn into velociraptors during that process. They make a sound that I only ever hear when trying to separate them from their eggs. Can't wait for your next post - love to Leslie!

Very well done, John, as always. I’ve sent it on to my wife, who was raised in Sonoma County, and to her relatives, Heather and Tom Chown, who still live there.

Chuck